(Still photo from Middleton Place video, courtesy Middleton Place Foundation)

Middleton Place gardens: creating this extraordinarily charmed place required the indispensable skills and relentless efforts of enslaved people who dug up its dykes and cultivated its rice fields using their millennia-old knowledge of agriculture. They also dug up and built its gardens and terraces.

Photo: Ty Collins

The Africans who made "Carolina Gold" worth its weight in gold

Ty Collins

Middleton Place is renowned as one of America's oldest landscaped gardens and the former headquarters of a regional rice economy spanning 19 plantations from North Carolina to northern Florida. It was home to Arthur Middleton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who helped frame language for American independence that favored gentrymen owning enslaved workers and land. And it was where enslaved Africans applied their traditional knowledge and skills to work that was essential to the establishment of the United States as a leading world power.

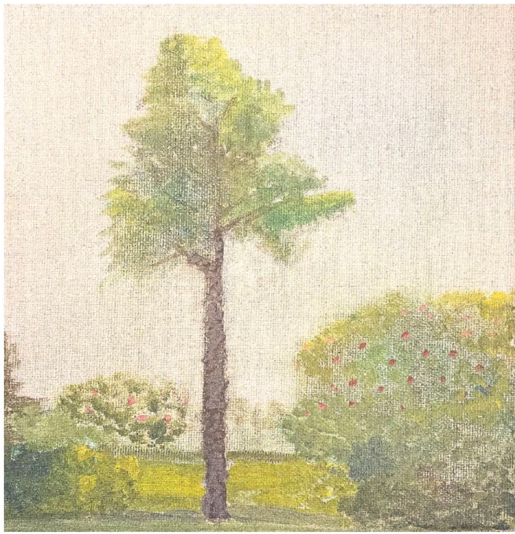

The English Middleton family's wealth and influence originated in their sugar cane plantation in Barbados. They enjoyed a lavish lifestyle there until the soil became depleted. Then Edward Middleton migrated to South Carolina with "seasoned Africans" who had well-honed agricultural skills. In switching to rice production, they depended on Africans purchased directly through the port of Charleston as well as those brought from Barbados.

The horrors of the transatlantic slave trade and the institution of chattel slavery were universal and relentless. After emigrating from Barbados, the Middletons established a plantation system in South Carolina based on a legal and social framework of dehumanization. Their initial attempts at sugarcane cultivation failed due to the local climate, but they achieved immense wealth by cultivating "Carolina Gold" rice.

Unlike cane, rice required extensive land preparation, demanding the application of millennia-old knowledge from the rice-growing region of Africa to replicate the Middletons' grand lifestyle in South Carolina. This knowledge was primarily sourced from what Europeans called the "Rice Coast," a region that included modern-day Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, and Charleston slave traders specifically sought out Africans from this region for their expertise.

And thus enslaved West Africans were the indispensable executers of Middleton family wealth .

Arrival in Charles Town was a traumatic extension of the Middle Passage. Survival for enslaved people was a daily struggle defined by psychological resilience and cultural preservation as resistance against a system designed for their exploitation.

The African ingenuity, skill and workforce that was the engine of the Southern economy

Middleton Place plantation is the site where an incredible story has yet to be fully told of how African people’s contribution to colonial and pre-Civil-War economies was essential. Each cash crop and product developed —like indigo, cotton, pine tar and tabby—were income generators along with the fabulous “Carolina Gold.”

The name "Carolina Gold" is more than a label. The "gold" refers literally to the distinctive golden hue of the rice hulls and metaphorically to the immense wealth it generated, transforming the Carolinas into a dominant force in the Atlantic market.

In addition to being what Gullah historian Kendra Hamilton calls “the nation state of rice,” South Carolina was among the originators of a systematic form of human “animal husbandry” that spread through the South, spurred by the end of the transatlantic slave trade. The practice of using men as animals to be bred like livestock and the women who could be exploited sexually for profit from offspring offered additional income streams that grew the American economy.

The Middleton’s profits were pumped into building a showcase home and estate influenced by landscape architect André Le Nôtre’s Versailles and the vision of horticulturist André Micheaux.

The natural and built environments of Middleton Place were developed by Africans in many ways.

Making “African bricks” from clay and sand

The Middleton homestead renovated the former John Williams homestead on that land. The new structures flanking the Williams’ manor house, the stable, spring house, carriage house and other buildings were made by men, women and enslaved children from what were called “African bricks.” Children’s fingerprints can be seen on the African bricks that were used in building the spring house and plantation chapel above.

European bricks were fired in a kiln by that time. In Africa, bricks were made from earth, water and binders like straw or grass and then left to harden in the sun. (Eventually the African brick making style was replaced in Charleston with bricks manufactured in a local plant with a kiln).

After the Civil War’s “unpleasantness” and an earthquake, bricks from devastated Middleton structures were repurposed into the garden wall, separating the farm side from the formal landscaped outdoor rooms.

Educator/activist Mamie Garvin Fields (August 13, 1888 – July 30, 1987), compiled a detailed historical record about her familial connections to Middleton Place in Lemon Swamp and Other Places, A Carolina Memoir. Mamie Garvin Fields’s husband, Robert Lionel Fields was one of the brickmakers and bricklayers who salvaged bricks from the devastated buildings at Middleton Place to use with bricks he made himself to fabricate the garden wall at Middleton. He taught his brick-making skills in a Burke High School program that evolved into the building construction diploma program at the College of Charleston.

Making tabby

Tabby is an African formulation for a mortar of limestone, clay, and crushed seashells that was used for making outbuildings and walls around the Middleton property. The tabby wall endures as a notable presence on the grounds of the pathway leading to the Plantation Chapel that separates the Mill Pond lawn from the pathway. The distinct African influenced structure has two upright pillars, establishing an entrance gate that leads to the edge of the pond. These remnants are rarely mentioned in site interpretation.

Boxing (tapping) trees

The Middleton Place enslaved workforce made products derived from pine trees, including tar, pitch and turpentine. The production of these goods called “naval stores” were integral to shipbuilding and other early industries and was one of the early economic drivers of the Lowcountry region. The method for extracting resin from pine trees, known as "boxing," involved making cuts in the trees to collect the sap.

Many enslaved Africans brought with them knowledge of resource extraction and forestry techniques from their homelands. Cultures in West and Central Africa had long-standing traditions of tapping trees to collect gums, resins, and saps for various uses, including medicine, waterproofing, and tools. This existing knowledge base would have been applied and adapted to the new environment and the brutal demands of the American naval stores industry, where it became a highly specialized and dangerous form of labor.

Landscaping

Chopping down brush, thickets and trees to make bridle paths, thoroughfares, footpaths and roadways, Africans shaped the formal spaces of the estate. The mounding of earth dug out for making reservoirs of spring water for tidal rice farming was repurposed into an elevation from the Ashley River, to create the parterre on a 17-foot rise (shown above). Unless pointed out, the grand reputation of Middleton Place as a landscaped wonder does not include appreciation of the buckets and boards and feet and hands and minds and traditions of the Africans who shaped it.

A view of the rice dyke looking across the rice field toward the Middleton plantation on the hilltop.

Author’s photo.

The busy Bardados port was central to the triangle trade between West Africa, the Caribbean and England. A prospect of Bridge Town in Barbados, 1695, Samuel Copen, London. Library of Congress collection

Geometric design of Middleton Place's terraced gardens was developed by Henry Middleton in the 1740s. Their creation was an immense feat of engineering and physical force, carried out by enslaved artisans. Photo: courtesy Middleton Foundation

“African bricks” were used to constuct the Middleton Place Spring House and chapel. (Photo courtesy Middleton Place Foundation) Emerging from the Middleton Place brickmaking tradition was 20th century brickmaker Robert L. Fields, the husband of South Carolina educator and civil rights activist, Mamie Garvin Fields who compiled a detailed historical record about her familial connections to Middleton Place in Lemon Swamp and Other Places, A Carolina Memoir.

.

Tabby wall at Middleton Place. Tabby is an African formulation. Tabby wall at Middleton Place. Author’s photo.

Carolina Gold

Left: watercolor of Carolina Gold rice stalk by Alice Huger Ravenel Smith (1876-1958)..

Far left: Women bearing backets of rice to boat headed for markets.

Both courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association via the History of SC Slide Collection of Knowitall Educational Series funded by S.C. General Assembly.

Boxing (tapping) tree. Loblolly pine at Middleton Place. Its resin was tapped to make one of the plantation’s auxiliary products: the naval stock.

Acrylic sketch by the author.

Building the Senegambian system of dikes and gates

Fresh water was needed for the rice fields and the Africans used their traditional knowledge to create the system. They used hand tools, buckets and boards to make the irrigation system integral to rice cultivation. Dikes are conveyors of water from one location to another. Think of it as a wooden water tunnel buried in the ground. Gates hold the water until water flow is needed to irrigate the fields in a tidal system of ebb and flow. When the tide goes out, the field is planted with rice seed and is covered by freshwater.

When the tide comes in the brackish water stays on top of the freshwater. Rice plants want their roots to grow in freshwater. The rice plant grows toward the sun. The systematic way to use a three flow series for getting the rice plant to mature is possible by lunar tides over time.

The tide goes out and the field is cleared of weeds and planted with rice seed (first flow). At the second tidal flow, weeds are pulled away from the rice stalk, and the long flow occurs during the longest period of rice plant growth. Fresh water was needed for the rice fields and the Africans used their traditional knowledge to create the system. They used hand tools, buckets and boards to make the irrigation system integral to rice cultivation. Dikes are conveyors of water from one location to another. Gates hold the water until water flow is needed to irrigate the fields in a tidal system of ebb and flow. When the tide goes out, the field is planted with rice seed and is covered by freshwater.

When the tide comes in the brackish water stays on top of the freshwater. Rice plants want their roots to grow in freshwater. The rice plant grows toward the sun. The systematic way to use a three flow series for getting the rice plant to mature is possible by lunar tides over time.

The tide goes out and the field is cleared of weeds and planted with rice seed (first flow). At the second tidal flow, weeds are pulled away from the rice stalk, and the long flow occurs during the longest period of rice plant growth.

Alice Huger Ravenel Smith watercolor of workers flooding the rice fields. Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association via the History of SC Slide Collection of Knowitall Educational Series funded by S.C. General Assembly

Middleton Place Gardens, 1930 postcard, J. J. Pringle & Lyons. Collection Smithsonian Institution

Video recreation of building the Senegambian system of rice field irrigation

Fresh water was needed for the rice fields and the Africans used their traditional knowledge to create the system. They used hand tools, buckets and boards to make the irrigation system integral to rice cultivation. Dikes are conveyors of water from one location to another. Think of it as a wooden water tunnel buried in the ground. Gates hold the water until water flow is needed to irrigate the fields in a tidal system of ebb and flow. When the tide goes out, the field is planted with rice seed and is covered by freshwater.

When the tide comes in the brackish water stays on top of the freshwater. Rice plants want their roots to grow in freshwater. The rice plant grows toward the sun. The systematic way to use a three flow series for getting the rice plant to mature is possible by lunar tides over time.

The tide goes out and the field is cleared of weeds and planted with rice seed (first flow). At the second tidal flow, weeds are pulled away from the rice stalk, and the long flow occurs during the longest period of rice plant growth.

The dikes were designed for damming fresh water from across the Indian Trail truncated underground into the Mill Pond and on to the Ashley River. This freshwater source was also used for making water features as it flowed from underground irrigation.

Rice harvesting

It’s mind boggling to imagine innumerable handfuls of rice kernels needed to fill one barrel!

The heavy laden kernels of rice have grown to maturity and are ready for harvest: threshing (shaking the grains from the stalk), winnowing with a winnow stick to remove rice from the stalk, husking the seeds with the sweet grass fanner baskets derived from African tradition, and cleaning rice kernels by putting dried corn kernels into a wooden mortar that they carved and using a pestle that they carved to polish the rice grains to get the Carolina Gold form of rice as the final labor intensive step in the three-step process. And they could only take a handful of rice at a time to polish the kernels.

It’s mind boggling to imagine innumerable handfuls of rice kernels needed in filling one barrel. (One estimate records 44 pounds daily, or five to six “pecks”a day for up to 48 quarts.)

Planting and maintaining their own gardens

Africans were not given land to grow their own crops on the irrigated part of the farm. Instead wattle fencing enclosed spaces for gardens behind the cabins in the enslaved “quarters.”

The produce they grew fed the “Lord Proprietor” and themselves. After a long day in the rice field, a patch of ground was tilled and okra, sesame, callaloo, peppers, and tomato seeds were sown. Tending the garden and harvesting fresh vegetables that were planted for their medicinal properties became another cycle of labor; however, the benefits were the reward of a family’s workload. Foraging for herbs and spices and berries in season added a variety of tastes and flavors. Wild game of possum, deer, rabbit, raccoon, fish and fowl were food staples, supplementing a limited, rationed diet of mush-like corn and water porridge. Cornbread was made when the master’s stone mill could be used by grinding corn kernels into a meal. Grinding it again and you get grits. Europeans thought this cereal made from corn was not for them but it was an excellent source of dietary fiber.

Clearing land, developing the estate, maintaining the formal gardens

The perpetual working the land involved clearing away large areas of trees that were used for making lumber for boards and boxes. Digging up large areas of land to make pits to collect freshwater above ground eventually became the reflecting pool, mill pond and butterfly lakes. Pathways were made for access to the buildings and a roadway for access to the dock from the stable yard.

Concurrent with this labor intensive work using only hand tools and brawn, the 50 men owned by Henry Middleton and the 50 men he acquired through Mary’s dowry, were the workforce that laid the foundation that would become the manicured,110 acre Middleton Place.

It took these at least 100 African men to shape the mounds of the parterre (terrace). The formal garden rooms evolved over three generations in the 18th and 19th centuries. And all the while, these men had a lot of domestic labor to maintain their own lives in their living quarters of scavenged wood and earth.

Presently, a staff of a dozen, or so, people hand manicure the estate. Power tools would damage the structural integrity of the heirloom shrubbery.

In these ways, wetlands were made dry and the dry land, wet, with freshwater for growing rice. Cypress swamps provided significant sources of wet earth for making building materials. Water-resistant bald cypress trees provided the wood for the rice dikes, along with other trees on the Indian trails around the swamp. The grove of hickory and loblolly, live oak, and magnolia trees were used for making hand tools and firewood.

The water-resistant wood of bald cypress provided replacement parts for the three schooners the Middletons owned for exports of rice and indigo to Charleston harbor and their received shipments of European household necessities.

We’ve been envisioning the punishing, exhaustive labor and the remarkable ingenuity, engineering and construction skills of the enslaved people at Middleton and that’s still ain’t the half of it, as they would say.

It took ten years and at least 100 African men to shape the mounds of the parterre (terrace). The formal garden rooms evolved over three generations in the 18th and 19th centuries. And all the while, a lot of domestic labor was needed to maintain their own lives in quarters of scavenged wood and earth.

African affinity with rhythms increased efficiency

The natural environment informed the labor skills and ways of working efficiently, shaping an African community on foreign soil, and transforming the land into the prosperous Middleton rice plantation.

Without a farmer’s almanac, the people knew the seasons by the waxing and waning of the moon and position of star constellations. Cloud formations announced the rhythm of work at hand.

Daily work rhythms are integral to West African cultures as shown in this clip from a 2005 film by Dutch filmmakers in Baro, a Malinke village in Guinea.

The enslaved men and women arrived at the rice fields ‘before day clean’ with tools they made from bamboo sticks, to remove weeds away from choking rice stalks. They worked by polyrhythms to keep rice-eating birds at bay. Children made rhythmic patterns as elders maintained a downbeat. Work songs and sorrow songs offered comfort in an transposed African culture of suffering and survival.

African work rhythms are exemplified in the stick rhythms used for making sounds to chase rice-eating bugs away from the growing rice stalk. And the very efficient technique of Middleton Place women and teenage girls to rhythmically plant rice seeds eventually led to the Charleston dance craze of the 1920s.

With a rice sack hanging on one shoulder, the girls and women made indentations in the soil with the toe and or heel of the foot, dropping a few seeds, and burying the kernel with their footwork in the ground. This method creates a rhythm: heel, ball (of the foot), toe. Heel, ball, toe. Heel, ball, toe.

The idea for tap dancing, as well as the Charleston craze, grew out of the rhythms of rice culture planting with African rhythms.

According to Middleton Place archives, a teenage girl, let’s call her Chloe, was responsible for the planting and upkeep of a quarter acre of land, and here she’s teaching her younger sibling how to sow rice seed. All of the field workers were teaching and learning from one another. Literacy through the oral tradition evolved by rhythms and music making while working. The enslaving languages of Dutch, Spanish and French and English formed to create a pidgin language that was spoken with African rhythms. Southern black pidgin English bifurcated into Gullah and Geechee linquistics in the coastal South Carolina and coastal Georgia region.

Gullah does not use the personal pronoun “I” and the letter “i” has an “e” sound. There are no final consonant sounds, so as Chloe instructs her sister, she says, “Chloe plan seed fas!”

Plan seed by e’ (the) foot

Meke hole’ right toe.

Tap down e’ right heel.

Meke hole e’ left toe.

Tap down e’ left heel.

Meke hole e’ toe.

Tap down e’ heel.

Lef foot

Righ foot

Righ foot

Lef foot

Plan rice seed!

The movements of foot sowing rice seeds developed into competitive dance moves that rice workers created to entertain themselves.

.

Flooding a rice field at high tide by lifting the dike gate. From Keystone View Company stereograph card, c. 1890, via the South Caroliniana Library.

Enlargement of the Keystone stereoscope slide

Women were involved in every aspects of rice cultivation.

Plowing rice. Engraving from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, November 1878. Courtesy of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History via the History of SC Slide Collection of the Knowitall.org Educational Series funded by the S.C. General Assembly through the K-12 Technology Initiative.

The Charleston dance is more rhythmic with punctuated beats and it engages the whole body in motion with articulated limbs flailing in all directions. The One! Two! One! Two! … is like sustained musical notation. The beat grows out of its name and origin: Charles-ton! Charles-ton! Charles-ton! Charles-ton!

Da-Da! Da-Da! Da-Da-Da-Da! Da-da! The sassy, ‘sashe’ (sasshay) gyrations of African women were expressions of freedom. The accentuated full-bosomed African women, arms akimbo, hands on hips, and elbows turned outward, freely swayed and kicked. European men were attracted to gyrating African women in a way they were not to their more restrained European women counterparts. Ownership over both guaranteed wealthy gentry the right to satiate wanton desires with these perceived ‘animals’ — behaviors they wouldn’t impose on their own wives and children. To save their daughters and sons from such carnal abuse, slave mothers submitted to the masters’ desires.

Bet my jigaboo jig dancer better than yourn!

Dancing for the master was forced submission to ‘do as you’re told.’ Planters waged bets: “Bet my jigaboo jig dancer better than yourn!”

For wealthy men, making bets in high stakes gambling was a favored pastime, often accompanied by drinking. The Middletons had the best dancers of all — another source of revenue to add to the coffers. Africa suffered, Europe profited, and the United States expanded.

Rice gate without side panels. (Author’s photo)

Considering the very tiny rice grain (encircled in red) popped from the tiny hull, imagine how many hands full of rice would be needed to fill one barrel.

Pounding rice in Orangeburg, SC. View of rice fanner tray on the left (Original photographer unknown; photo via Carolina Gold Rice Foundation)

Mortar and pestle carved in the African tradition by enslaved artisans at Middleton Place. These utensils were used for polishing the rice. (Author’s photo)

Field shouts

James P. Johnson was a northerner who based what jazz historians consider to be the rhythmically advanced “Carolina Shout” in southern black praise and dance movements. “I find I have a strong feeling for these dances that goes away back,” he said. The “dances” to which Johnson referred included field shout and ring shout movements.

Chloe raises her foot to tap seeds into the ground with her toe. (ecollective)

A southern “flapper” doing the Charleston dance based on rice seed foot planting motions to music played by the Jenkins Orphanage Band in Charleston SC, 1926. Photo via Charleston Public Library.

Stereograph view of farmers, including women, hoeing rice field.

Oil sketch of Horse Savanna, a swamp across the Indian Trail from Middleton Place where enslaved rice workers lived. The strip of soil is the footpath through the wetland to the African-styled village.

The Middleton “lord proprietors” did not provide housing for the enslaved workers. The workers depended on their own resourcefulness to construct shelters using available materials such as grass, sticks and mud.

Imagine a plantation that made even the majestic Tara in ‘Gone With the Wind’ look like a small farm – that was Middleton Place before the Civil War.

There were two quarters for the enslaved people.

The house servants lived on “Slave Street” near the manor house.

Across the Indian Trail, the field workers lived in an African type village with a circular pattern of “lean tos” that they built from scavenging trees and grasses for the roofs and combining a mix of earth, sand and seashells to make a “tabby” mortar for the foundations. The village was called “Horse Savannah” because that’s where the livestock (cows, sheep, pigs) and the horses and water buffalo were corralled and cared for by the villagers.

Spring, 1843, Horse Savannah

Sweep the yard out on the way to the fields

And sweep the way back towards their homes for the night.

Sweeping the yard was a form of home security: a way of tracking footprints of people (including rapacious men) and scavengers who shouldn’t be there. It also kept the communal living space clear.

The huts in Horse Savannah were so small the villagers mostly lived in the outdoor circular space — making crafts (including tools of iron and wood at night to facilitate their own days’ work), telling stories, singing, dancing, (African rhythm beats), thigh slapping (hambone) with chanting, singing and hand-game clapping in call and response.

Pat-a- cake, pat-a- cake,

Mek’um cake pan

Meke pancake

Fas as ye can… .

The elders kept the downbeat and the children learned to keep rhythm time with sticks and gourds. They danced in circles clockwise to praise music and pranced counter clockwise humming sacred songs and sorrow songs to acknowledge deceased villagers.

They also found refuge from working between “can't see to can’t see” in spiritual practices. Group singing of sacred songs and chanting spirituals sung in cadences had a cleansing, restorative effect.

The villagers kept gardens near the huts. In addition to the masters’ mush doled out for the animals and themselves, the villagers created savory okra stew with other vegetables from their gardens served over rice. This one-pot meal was an African staple, known as okra soup in Charleston, gumbo in New Orleans, and jambalaya in the Caribbean.

It is important to point out that African rituals were forbidden on plantations. The hours between 12 midnight and 2 am were opportunities to commune with the spirits, bury the dead, name new born babies, pray and celebrate life in traditional ways.

A kettle turned upside down in the center of an area cleared away and was thought to muffle their ‘secret’ sounds in an enclosed outdoor sanctuary anchored by trees.

“Seeking” was a ritual of passage for adolescents to embrace the imagination of spiritual belief. Young people were given a space in the woods to seek the ‘spiritual’ being within, until the imagined Source is known and affirmed.

“Seeking” was a way of finding the spirit of freedom beyond captivity and to open a dialogue with ancestors on the path to adulthood. Overcoming fear in the darkness, in the woods, away from society, was the pathway for exploring the inner self.

The practice of "seeking" also was a way to maintain a spiritual dialogue with ancestors, who were believed to guide and protect the enslaved. This connection provided a link to their African heritage and a source of strength in the face of immense hardship.

Back in the community, holding hands in the circle bound believers to experience the oneness within the unseen realm.

Special occasions of joy found in ‘jumping the broom’ wedding and baby naming ceremonies marked their transitory escape from an economy based in suffering.

Horse Savannah arts, crafts and material culture

The material culture of Horse Savannah was created out of the surrounding environment. The children making toys from rice stalks used like twine to connect discarded, ripped up feed bags into handmade “twiss up” dolls. It’s my understanding that Savanna Horse villagers used feed bag cloth for adapting the indigenous peoples’ use of a plant that the Europeans called “asafoetida” for what the native people viewed as “medicine bags" and the English called “poultices.” Africans living on Horse Savanna interacted with transient indigenous peoples. Plants were central to the folk medical beliefs of nomadic tribesmen and Africans. American folk medicine is a hybrid of folkways that use plants as a form of first aid and prevention.

Because drumming was forbidden, the villagers used seeded gourds as musical instruments. Bamboo was grown as a barrier to keep wildlife away from the formal grounds, but they were also rhythm sticks for music making. Bamboo walking sticks were carried by the elders who led children through rough terrain. Tapping the ground on the footpaths alerted the crawling things that humans were nearby. Reptiles fear humans and they are equally afraid of them. All animals live by instinct in harmony with nature. European men cleared nature away to control the land, conquering anything they could not control was a threat to them. Protection from harm means total annihilation.

The Horse Savannah villagers used dye from a plant they sowed and harvested like indigo (a green plant with a red flower, yielding a green dye.). Wild berries, various tree bark, or iron gall ink, used for making the color black to dye cloth, were foraged. (Nails in water with wasp nesting material made an indelible black color dye, before india ink was available via the silk route.) Pokeberry weed was another source for making a purple dye from the juice of the dark bluish berry.

Raw fabrics in this period in history were tinted in a dye bath for color variation in cloth. Africans knew about plant fibers for coloring into woven geometric patterns. But wearing the colors and patterns of tribesmen was forbidden. Raw linen and rough cotton were rationed to ‘slaves’ once a year. Europeans purchased their rich, silk fabric wardrobes from France and Great Britain. Africans were made to wear rationed clothing until they were threadbare and patched over and over. Clothing scraps had a renewed life in rag quilting items.

The creativity and resourcefulness of the enslaved Middleton communities are expressions of both African traditions and multi-heritage African American folkways that evolved into crafts and art forms through resourceful interactions with nature.

Grapevine baskets were hand crafted items used for various purposes. In the basket shown here are a seashell for cutting bark from trees, a bamboo stick (stick pairs made African rhythms), and the sweetgum ball was a fire starter. Soaked in oil, seed pods were a source for maintaining a fire. Think about a bag of charcoal needed for grilling. Throw it on the grill and the fire for cooking is replenished.

The “seeking” practice had a counterpart in African wilderness retreats such as “mfinda.”

Here’s more information about that tradition.

Women with brooms of bambusa (a bamboo species) in Belton, South Carolina, 1899. Photo: US Agriculture Department

Fictiliuvaforu in quibus cibucoquunt (The Beauty of the Earthenware Vessels in Which They Cook Food), 1590 engraving by Theodor de Bry. Credit: The Mariners' Museum, Newport News, Virginia

The Africans at Middleton Place plantation lived near a path called the “Indian Trail” and cooked communally outdoors in a large pot. This research documents how indigenous food ways influenced and/or were complementary with African food ways in the Carolina coastal plain.

Detail of carved walking stick with poultice. The bamboo stick was crafter by Middleton Place blacksmith, Jamal Hall, and embellished by the author.

Grapevine baskets were fashioned by children as young as five-years-old. After every rainfall, children were given the task to harvest the wet grapevine for making a basket that was used to gather okra from the garden, eggs from the chicken coop and vegetables from the garden for the communal cookpot. These hunter-gatherers were making crafts as the need arose and nature was at the ready, providing trees and roots and leaves, and shells.

Replica of “twiss up” doll made by the author of rope ,rag pieces, twine and seasoned herbs.

Replica of asafoetida bag made by the author.

Contemporary expression

Basket contains a piece of seashell for cutting bark from trees, a bamboo stick, and a sweetgum ball.

At Middleton Place today, as a way of learning how the Horse Savannah villagers created items from the surrounding natural environment, a student crafts roses from bamboo stalks.

Bundle of pine sprigs for making pine oil tea.

The Middleton Oak or “trading tree” was known as the midpoint between Charleston Harbor and Summerville.

Lord Proprietor Henry Middleton owned land and access to the waterways to the right of the tree. His son, Arthur acquired land and access on the other side of the tree and the seven mile of waterways toward Summerville on the left.

Oil sketch by the author

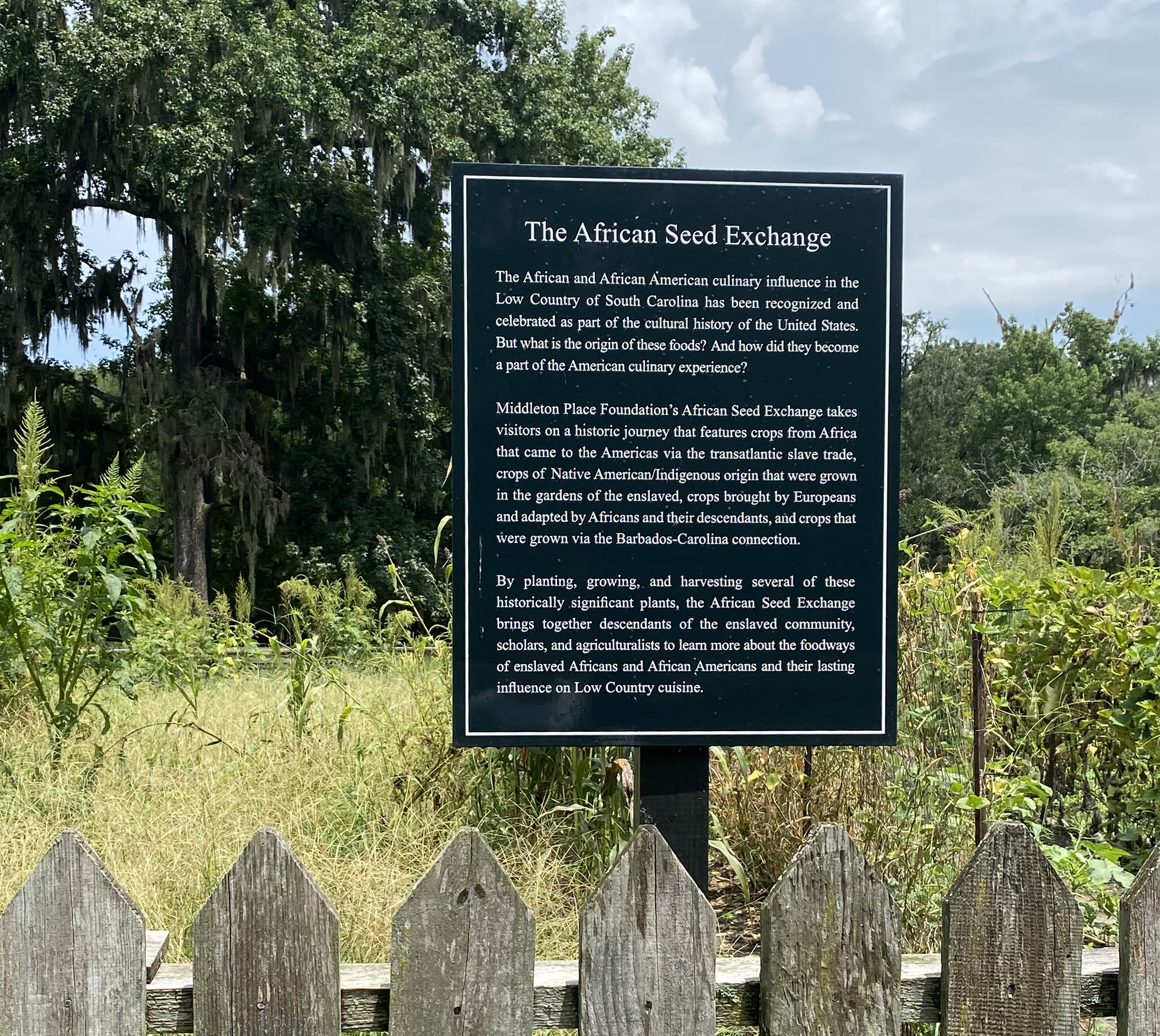

African Seed Exchange education pavillion at Middleton Place, 2024. Author’s photo

Near the Middleton Place restaurant’s rear are two grave markers that are referred to as the “slave cemetery,” but recognition of the dead from four generations of enslavement at Middleton Place is a gesture of representation.

My dubious honor as a descendant of formerly captive rice cultivating Africans at Middleton plantation has been a source of inspiration because I am among a group of descendants of enslaved people who are reframing the public history of the place and this article is the first in a series that is part of that effort. In this three-part series, we are expanding the narrative to include the significant contributions of our ancestors to the American democratic experiment which the Middleton Place National Historic Landmark now represents. History is colored by the complexion of the writer. As the African proverb reminds us: “Until the lion learns how to write his truth, every story will glorify the hunter.” ~ African proverb

The second article will cover the descendents ASE’ project which includes seed sharing, planning and planting a descendants garden of plant specimens grown with these seeds, benches commemorating our ancestors and various forms of community engagement

African origins: okra, yam, black-eyed peas, Sea Island red peas, Barbadian callaloo, scotch bonnet peppers, broadleaf thyme, and Native American ginger. Foodways keep our ancestors in the conversation and planting carries the folk traditions forward.

The third and final article of this series will trace the history of the interaction between the Middleton Place white and black families and the development of the now legendary gardens through the perspective of a tour of the garden conducted by a Middleton Place horticulturist Sidney Fraizer, and myself, a Middleton Place interpreter. Sidney Fraizer is the VP of horticulture at Middleton Place.

Sidney Frazier, master gardener & VP of horticulture, has dedicated over 46 years to overseeing the care of the oldest landscaped gardens in America at Middleton Place. This is the time of year when camellias take center stage, providing vibrant color in cold winter months. The camellias at Middleton Place are special because they are some of the oldest in America, first planted on Henry Middleton’s parterre in the late 18th century.

Frazier, dubbed “The King of Camellias,” leads lively workshops, covering several aspects of the camellia plant, from its origins in Asia and its various forms to care and maintenance. Expect expert advice in planting, water, pruning, fertilizing, propagating, and disease identification and eradication.

Middleton Place vice president of horticulture, Sidney Frazier.

Photo courtesy of the Middleton Place Foundation journal.

Ty Collins is a public historian and associate with the Black & Brown Interpreters Network (BBIN). As current president of the Charleston-area branch the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, the 110 year-old organization of Carter G. Woodson, founder of Black History Month, he continues Woodson’s tradition by creating and disseminating knowledge about the history and cultures of African and African-descended peoples.

Ty Collins with his aunt, Mamie Garven Fields, author of Lemon Swamp that recounts the African American Middleton residents and their descendants.

Photo from a 1995 book signing. Collection of the author.

Top right: Eliza’s House, a freedman’s cottage named after the last person to live in this house, Eliza Leach, who died in 1986 at the age of 94, Eliza's House is much the same as it was for the past 100 years. Photo by K. Armstrong for the U.S. National Archive

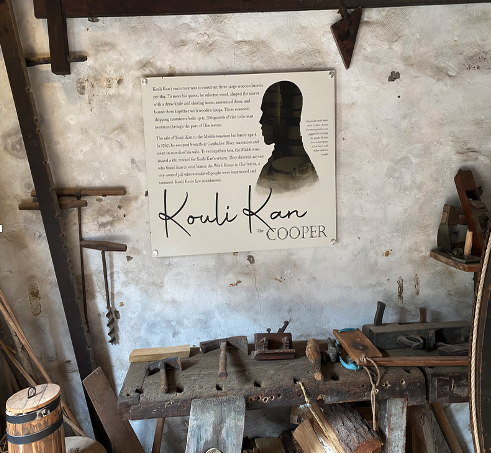

Above: Middleton Place photo of artifacts and didactic panel for barrel maker Kouli Kan for its its “Beyond the Fields” interpretation.

Below: Indian Trail also known as Ashley River Road (Highway 61). Oil painting by the author.