Sowing the seeds of black horticultural history into a comprehensive field

Carter Cue

The African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium held in Durham, North Carolina in 2024 and 2025 brought together home gardeners, forestry specialists, horticulture professionals, florists, food crop cultivators, college students, nature lovers and historians across a spectrum of demographics. The symposium’s primary goal was to educate and encourage exchanges among attendees and the general public about the mostly unexamined history of African Americans in horticulture and their continuing legacy.

The symposia’s interpretation of “horticulture” — the art and science of growing fruits, vegetables, flowers, trees, shrubs and ornamental plants — centers on this definition but expands to include topics such as the prevention of land loss by black people in the South.

The impetus for both symposia was the life story of the little-known educator, transnational activist and gardening enthusiast, Madie Hall Xuma, a native of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Alfred B. Xuma, South Africa’s first black medical doctor and early president of the African National Congress (ANC) in the 1940s Apartheid era is better known than his plant loving wife, Madie.

Alfred B. Xuma received his undergraduate degree in agriculture at Tuskegee Institute under the auspices of Booker T. Washington and was the subject of Steven Gish’s 2001 biography, Alfred B. Xuma: African, American, South African.

As university archivist at Winston-Salem State University I met Steven Gish when he was researching and writing about A.B. Xuma. The WSSU Archives held materials on his wife and Winston-Salem State University alumna, Madie Hall. Hall Xuma was such a dynamic, well-rounded personality I inquired of Gish if he had any intention of writing a book on her. He said he did not; his next book would focus on Bishop Desmond Tutu.

In 2023 I received a call from Steven Gish informing me that Wanda A. Hendricks’ book, The Life of Madie Hall Xuma Black Women's Global Activism during Jim Crow and Apartheid had just been published. After contacting Hendricks, we had a community lecture and book signing event in 2024 sponsored by the Durham County Library. Hendricks is Distinguished Professor Emerita, History, University of South Carolina.

Madie Hall Xuma, transnational gardener

Wanda A. Hendricks’ biography on Madie Hall Xuma highlights Xuma’s friendship and interactions with notables such as Mary McLeod Bethune, Harlem Renaissance poet Anne Spencer, W.E.B DuBois, Kwame Nkrumah first President of Ghana, Paul Robeson and many others. Hendricks’ book also sheds light on Hall Xuma’s racial uplift efforts with the YWCA, AME Zion Church, National Council of Negro Women and her work as the founder and first president of the Women’s League of the ANC.

Interspersed among the book’s text and footnotes were details indicating that Madie Hall Xuma was an enthusiastic gardener whose pre-marriage Winston-Salem, North Carolina home had a sprawling ornamental garden replete with a koi fishpond. In 1931 she established Along the Garden Path, Winston-Salem’s first African American garden club.

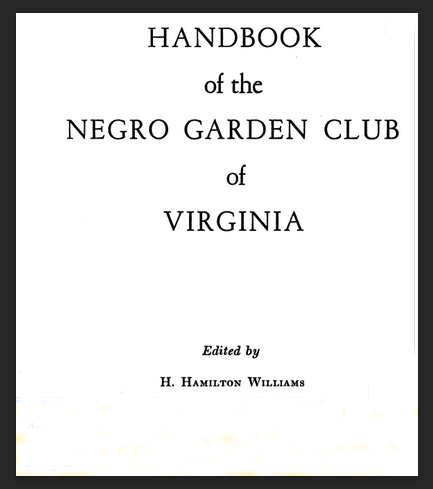

Hall Xuma’s enthusiasm and organizational prowess led her, with the assistance of gardening pioneer and Hampton Institute professor and alumnus Asa Sims, to found the North Carolina Federation of Negro Garden Clubs (now known as the North Carolina Federation of Garden Clubs) on the campus of North Carolina A&T State University in 1935. Three years earlier in 1932, Asa Sims had helped establish a similar black gardening organization, the Negro Garden Clubs of Virginia, which published the Handbook of the Negro Garden Club of Virginia edited by Hampton Institute graduate Harold Hamilton Williams.

While I was familiar with a few Jim Crow-era black garden clubs and horticultural experts in North Carolina, effervescent gardening historian and storyteller Abra Lee made me aware of the various black gardeners and horticulturalists in Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, North Carolina and elsewhere and their interconnections. While my research on black gardening history was focused on North Carolina, through Abra Lee I learned of H. Hamilton Williams and Anne Spencer, both of Virginia, as well as North Carolinians Annie Mae Vann Reid and Asa Sims — most of whom had some level of interaction with Madie Hall Xuma when she was the first president of the North Carolina Federation of Negro Garden Clubs.

In the same way that gardeners often share plants, seeds and gardening tips, Abra Lee introduced me to her friends and colleagues Shaun Spencer Hester, executive director of the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum, Lynchburg, VA, and granddaughter of Anne Spencer; Wambui Ippolito, garden designer; Mike Gibson, topiary artist; and Teri Speight, garden writer, author, all of whom would play significant roles in both the 2024 and 2025 symposia.

The 112-year old gardener Catherine Ferrell, still full of vitality, was honored at the 2024 African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture symposium

The first symposium was not only the first in a series but the first conference ever held on African American ornamental horticulture history and its continuing legacy. It took place on Saturday, March 30, 2024 in Durham at the Hayti Heritage Center in the historic black community of Hayti (pronounced Hay-tie, a name inspired by Toussaint L’overture’s independence movement).

The symposium opened with a flag processional of members from the North Carolina Federation of Garden Clubs (formerly the North Carolina Federation of Negro Garden Clubs) followed by Allison Kalloo singing the Federation’s anthem, “O’ Garden Green,” and recognition of Durham resident and North Carolina’s oldest gardener, 112-year-old Catherine Ferrell with a proclamation from the Durham County Commissioners.

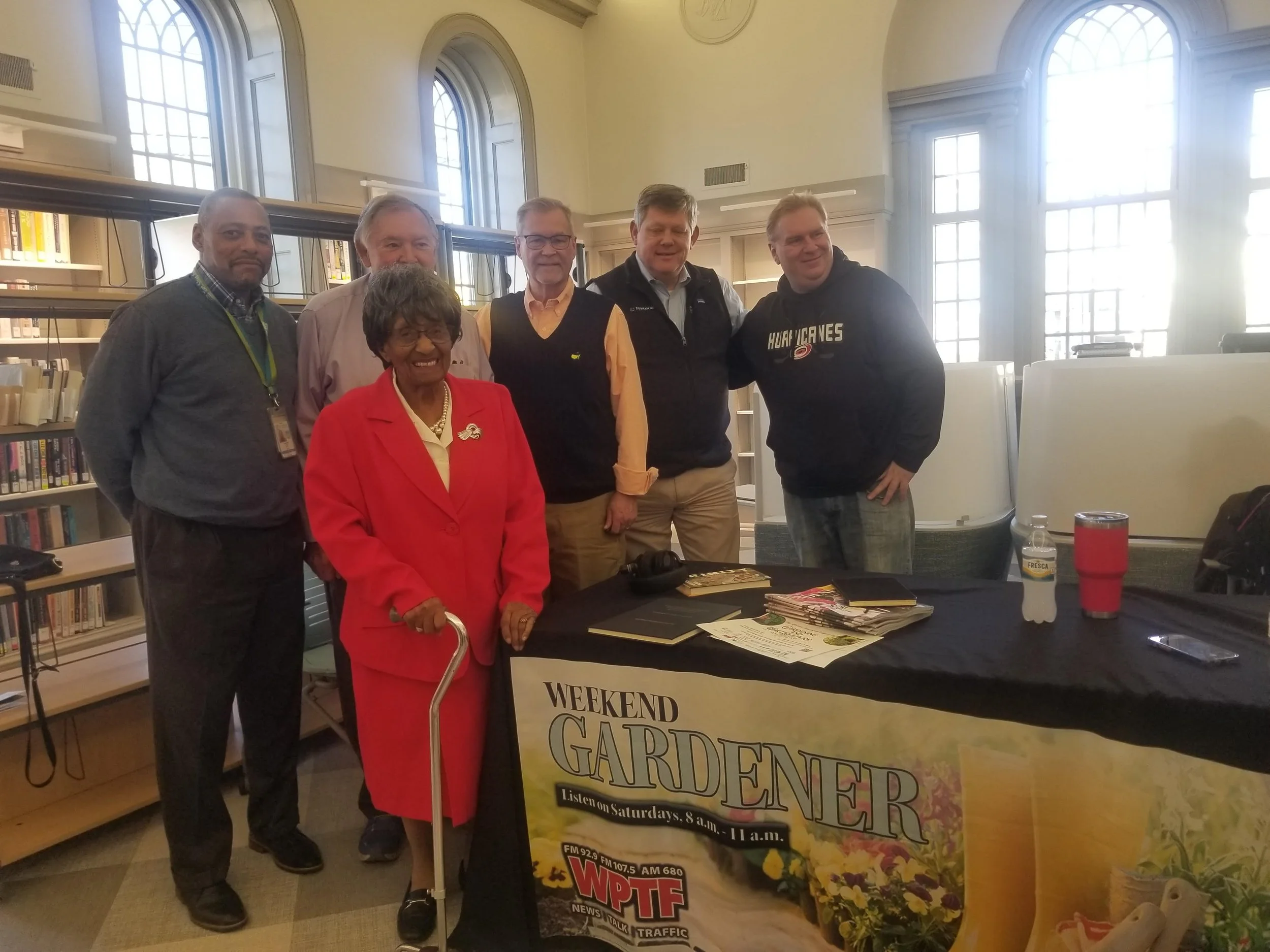

A few weeks earlier, Catherine Ferrell (born Oct. 10, 1912) had joined me as a guest on this episode of The Weekend Gardener radio show and said she still loved to grow butter beans in her garden and noted that collard greens and sweet potatoes are also her favorite veggies!

.

Keynote address: Hidden in Plain Sight

The 2025 AALGH symposium

Strip away the background and these men could have been could have been hangin’ in the barber shop, shootin’ the breeze, but turn up the volume and you’d hear them talking about the fine points of caring for trees and the art of topiary on “The Wisdom of Trees: Urban Forestry and Black Land Ownership in the Subaltern South” session of the 2025 African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium. Photo: AALGH

The processional and performance were followed by proclamations from the Durham County commissioners recognizing topiary gardener Pearl Fryar and orchid cultivators John Hope, the noted historian, and his partner, Aurellia Whittington Franklin. Fryar attended North Carolina Central University and Central’s Dean of the College of Health Sciences, Mohammad Ahmed brought greetings on behalf of the university. Further remarks about John and Aurelia Franklin were made by Duke University Chancellor Vincent E. Price. Durham playwright Ira Knight was master of ceremonies.

Carol Henderson, president of the New Hope Bird Alliance introduced the presenters for plenary session one, “The Wisdom of Trees: Urban Forestry and Black Land Ownership in the Subaltern South”: moderator Darrell Stover, poet and head of the NC Science Museums Grant Program, Alton Perry, director of the Roanoke Cooperative Sustainable Forestry and Land Retention Project; Tyrone Williams, a third generation NC landowner and owner of Fourtee Acres Farm; and topiary artist Michael “Gibby Siz” Gibson. They explored the role of urban forestry in promoting black land ownership within racially hostile social and political environments.

African American Dance Ensemble performing at 2025 African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium. Photo: AALGH

The symposium activities were available to deaf and hearing-impaired communities via the North Carolina Interpreters Network.

The symposium began at 9:30 am, drawing to a close at 2:30 pm with final remarks from Angela Lee, executive director of the Hayti Heritage Center, and Kavanah Anderson, director of learning and community engagement at Sarah P. Duke Gardens. To conclude the day's events, attendees were enthralled by Ajusher, an indigenous-led musical group committed to sharing their culture’s music and movement with the public.

Despite the resoundingly enthusiastic reception from the 700 online and in-person attendees – and our generous sponsoring organizations – the planning committee decided to skip a year for the African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium. The considerable time, effort, and energy invested in organizing such an event led us to this choice. With the additional time for planning, we will resume the symposium in 2027 with an even more robust and enriching experience for all garden and nature lovers.

The symposium activities were available to deaf and hearing-impaired communities via the North Carolina Interpreters Network.

The symposium began at 9:30 am, drawing to a close at 2:30 pm with final remarks from Angela Lee, executive director of the Hayti Heritage Center, and Kavanah Anderson, director of learning and community engagement at Sarah P. Duke Gardens. To conclude the day's events, attendees were enthralled by Ajusher, an indigenous-led musical group committed to sharing their culture’s music and movement with the public.

Despite the resoundingly enthusiastic reception from the 700 online and in-person attendees – and our generous sponsoring organizations – the planning committee decided to skip a year for the African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium. The considerable time, effort, and energy invested in organizing such an event led us to this choice. With the additional time for planning, we will resume the symposium in 2027 with an even more robust and enriching experience for all garden and nature lovers.

From the editor

A green thumb and an archivist’s mind

Carter Cue, adult services librarian at the Stanford L. Warren branch of the Durham County Library, feels strong allegiance to both his community and the natural world and is merging those affinities through organizing the African American History of Gardening and Horticulture symposia and other public programs.

A native of Durham, Cue holds a B.A. in English from Winston-Salem State University and an MLS in Library Science from North Carolina Central University. His previous position was university archivist at WSSU’s O’Kelley Library.

Cue’s curiosity extends far beyond library stacks and archive boxes, encompassing design, architecture, visual and performing arts, anthropology, and textiles. He is a member of the Nasher Museum Friends Board and has curated exhibitions, such as "Reading Black Art" at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

"All of my relatives were farmers," Cue notes, recalling his second great-grandfather's claim against his last master via the Freedmen's Bureau:

“His claim against his former master, like the majority of the other claimants in the Freedmen Bureau records, was to be compensated for "1/3 of the crop". When planters lacked sufficient cash to pay their workers (newly emancipated enslaved Africans), they were permitted to pay a share of the crop at the end of the season, an arrangement that anticipated the sharcropping and tenancy systems that characterized North Carolina's agricultural economy for the better part of the next century.”

Cue also reflects on his youth, a time when growing one's own food was commonplace, particularly among residents of Durham's housing projects and he remembers black women’s flower clubs in the community.

He also recalls a black men's garden club in Winston-Salem NC, when he was a student at Winston-Salem State University in the 1980s. The club’s name, “The Prince’s Feather,” was elegant with a light touch and slightly cocky.

The history of African American garden clubs wanes in the 1960s. Their contemporary iteration is diffuse with black people enjoying many aspects of personal gardening and becoming horticultural professionals.

With a strong interest in ornamental horticulture, Cue has had the privilege of transforming his own community's landscape, removing diseased trees and shrubs to start anew — (“privilege” because he is a member of the community’s home owner association which has guidelines). While he embraces traditional methods, like cultivating a long English cottage garden herbaceous border, he also adapts, growing tomatoes and herbs in pots due to HOA restrictions. He's no plant snob, happily seeking deals at big box stores.

His hort hangouts include the renowned Sarah P. Duke Gardens, the NC Botanical Garden, the JC Raulston Arboretum, and the Juniper Level Botanic Garden.

He’s also an art collector and archivist. These days, he quips, he's probably more interested in owning plants than paintings and prints because the plants are much cheaper than 30 years ago when the art establishment gate keepers' gates in New York City were broader but much of the rest of the mainstream art world was slower to catch on.

Reflecting on how his visual arts and hort interests converse, he says that Nefertiti Goodman, “a fabulous printmaker,” is doing some great work incorporating an abundance of flowers, nature motifs and general horticulture in her prints and paintings. And he recalls first seeing the brilliant abstractionist painter, Freddie Styles on HGTV “talking about his garden even before I met him in person at his studio. At that time, over 20 years ago, Freddie was using the foliage and roots from the plants in his garden to paint on canvas and paper.”.

Beyond the beauty of the ornamental garden, Cue is deeply concerned about environmental issues. Witnessing his Zone 7b shift to 8a and experiencing increasingly hot and humid springs and summers in North Carolina, he views climate change as "our greatest existential threat." He worries about the legacy his generation leaves for his great-nieces and nephews, recalling futurist Jacque Fresco's stark warning 30 years ago when they were discussing Fresco’s Venus Project and theories of a “resource based economy.” Fresco said that money, your education, material goods etc. didn't mean anything if your planet, air, water and land is polluted. Cue also cites Douglass Rushkoff's Survival of the Richest as a book that provides a crucial contemporary perspective.

Cue believes in humanity's innate connection to Mother Earth, a relationship he observed firsthand during his time working and living in African countries under the auspices of the United Methodist Church. He also visited other African nations as a tourist and developed a particular interest in Southern Africa and the liberation strugges of frontline nations Mozambique and Anglola.

He emphasizes the wonder and awe found in observing nature, a connection understood spiritually, psychologically and biologically by indigenous populations and three-quarters of the planet's human life.

What about the remaining fourth? Many progressive people in the global north also are strongly reaffirming that connection to the Earth. It’s mostly leaders of the moderate to far right camps who are cut off from this vital connection or have an attenuated connection with it. Maybe the healing of the great MAGA-MAFHP (make American fulfill her potential) rift can swell up from the people who live on the land and love her, a lot of them are in red states too.

For those inspired to cultivate their own green spaces, Cue advises simply, "If you want to plant a garden or put in a mixed border hedgerow then do it." He readily shares his favorite online resources, including Horttube with Jim Putnam, and looks forward to discussions with authors like Jarvis McInnis, whose book Afterlives of the Plantation: Plotting Agrarian Futures in the Global Black South will be featured at his library. (See announcement above.)

Carter Cue is promoting an understanding of our human place within the living world that’s spreading out in ripples from his local community and merging with similar energies to help bring this beauty and healing to all.

Freddie Styles (AYA Series #3) collage on canvas, 24 x 36” Photo: Courtesy September Gray Gallery

Flower Ladies of Chapel Hill on Franklin Street, campus of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1960s. Photo source.

Below left: Madie Hall Zuma in front of her home in Winston-Salem, NC.

She coaxed the ivy to grow in swirls around the porch rails and post.

Below right: Madie Hall Zuma working in her garden.

Dorothea Lange’s 1939 photo of a North Carolina sharecropper’s cabin with this caption: “Note also flower garden protected by slender fence of lathes” on Paul Mullins Archeology and Material Culture site. Wild flowers also are growing in the yard. Photo: Farm Security Administration, Library of Congress)

In 1927, Ethel Earley founded Big Lick Garden Club in Roanoke, VA, according to research by Meredith Henne Baker supported by the Library of Virginia. Read more here.

Book News

AALGH symposium organizer Carter Cue presented Jarvis McInnis and Savi Horne discussing McInnis' new book, Afterlives of the Plantation: Plotting Agrarian Futures in the Global Black South, on September 6, 2025 at the Stanford L. Warren Library, in Durham, NC. (More about Savi Horne of the Land Lost Prevention Project.)

The book shows how black individuals, particularly in the U.S. South and Caribbean, transformed former plantation lands into spaces for self-determination through agrarian practices and institutions like the Tuskegee Institute. This reframes black modernity by emphasizing rural settings, rootedness and agricultural liberation as central to imagining alternative futures beyond the plantation's legacy.

Carter Cue

Carter Cue’s horticultural and visual arts interest combine in works by his botanically-oriented artist friends, Nefertiti Goodman and Freddie Styles.

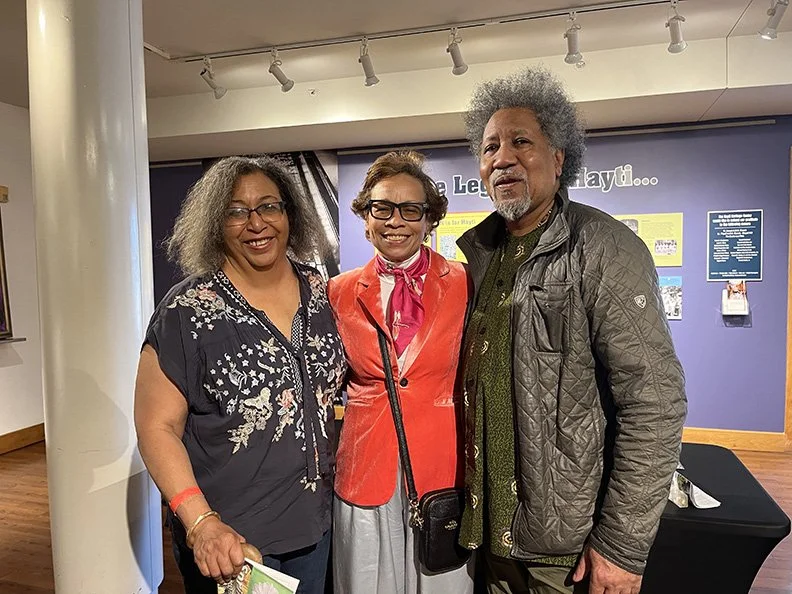

Horticulturalist and scholar Kendra Hamilton (left) was pleased to meet Shaun Spencer Hester, granddaughter of poet Anne Spencer and executive director and curator of the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum in Lynchburg, Va., and to reconnect with Darrell Stover, director of the science museums grant program at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences. Photo: Kendra Hamilton

Session two, “Anne Spencer’s Garden: Understanding Black Women’s Gardens as Emancipatory Spaces,” was moderated by WUNC radio host Leoneda Inge in conversation with author and Fullbright Scholar Zelda Lockhart; Noelle Morrissette, UNC Greensboro full professor of English; and Shaun Spencer Hester, executive director of the Anne Spencer House, delved into the intricacies of Spencer’s extraordinary life. Spencer was a Harlem Renaissance era poet, activist, gardener and the first black librarian in Lynchburg.

Noelle Morrissette’s book Anne Spencer: Between Worlds provides a new interpretation of Spencer’s expansive life and imagination through her archives, particularly manuscripts from 1940 to 1975.

The symposium concluded with a keynote address by Abra Lee, horticultural storyteller and director of horticulture at Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta Georgia. Lee’s captivating talk was “Hidden in Plain Sight: The Legacy of African American Gardeners, Horticulturalists and Growers.”

Her interactive presentation introduced symposium attendees to little known African American plant people, nursery owners, florists and botanists.

The second session was brought to order by dentist and Durham Library Foundation chair, Desiree T. Palmer. Justin Robinson, an award-winning musician and herbalist was moderator and presenters were award winning Kenyan garden designer Wambui Ippolito, botanist and social media star, Derek “The Chocolate Botanist” Haynes and author/garden writer Teri Speight.

Their discussion ranged over the past and present ethno-botanical worlds of immigrants and enslaved Africans. Speight, author of Black Flora: Inspiring Profiles of Floriculture’s New Vanguard had copies of this 2024 book available for sale and autographing.

Alfred and Madie Hall Zuma, 1955.

Below:

Book and garden club of Wilson, NC, 1948. More details about the Wilson club here.

The Negro garden clubs of North Carolina had a rural antecedent as shown in the Dorethea Lange photo on the left.

Carter Cue’s second great grandfather is listed in this talley of sharecropping farmers.

Anne Spencer with husband, Edward, and their grandchildren in the garden, June 1929. Photo: the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum, Inc. in the Encyclopedia of Virginia.

Catherine Ferrell, 112-year old gardener during the 2024 “Weekend Gardener” radio show airing from the Durham County Library's Stanford L. Warren branch Library. Carter Cue is on the left.

Afro-Ecologies: Ethno-Botanical Healing, Farm Foodways, and Floriculture in Black Southern Landscapes

In session one of the 2024 symposium, “Afro-Ecologies: Ethno-Botanical Healing, Farm Foodways, and Floriculture in Black Southern Landscapes,” panelists Derek (“The Chocolate Botanist”) Haynes, musician and herbalists Justin Robinson, floral designer Rev. Bettye Jenkins and flower farmer Cheryl Gibson discussed Afro ancestral plant wisdom methodologies used in healing, birth and death rituals, and the increasing disconnection from nature by a younger generation as a result of digital dependency including social media consumption.

From left,: Bettye Jenkins, owner/designer of Bettye's Flower Designs and a descendant of one of the original "Flower Ladies" of Durham; Justin Robinson, founder of the Earthseed Collective; Derek Haynes, "The Chocolate Botanist"; and Cheryl Gibson, owner of Vine and Branch, a boutique flower farm in Durham. Photo: Kendra Hamilton

Anne Spencer’s Garden: Understanding Black Women’s Gardens as Emancipatory Spaces

“The Wisdom of Trees: Urban Forestry and Black Land Ownership in the Subaltern South” session with Darrell Stover at lectern, sign language interpreter, Valerie McMillan and panelists Mike Gibson, Tyrone Williams and Alton Perry.

Beyond Borders: the ethno-botanical and horticultural influence of Africans, African Americans and immigrants on the American Landscape: Justin Robinson, herbalist; Kenyan garden designer Wambui Ippolito; botanist and social media star, Derek “The Chocolate Botanist” Haynes; and author/garden writer Teri Speight.

Following a delicious buffet lunch for attendees the third session, “Centering African American Narrative Stories in Contemporary Environmental Literature and Media” got underway with presenters being introduced by Shakita Holloway, horticultural technician at the North Carolina Botanical Garden. They discussed how African Americans writers and conservationists have reimagined and attempted to interpret African American and peoples of color interaction with nature and the greater outdoors.

The panel was moderated by the aforementioned Zelda Lockhart whose recent novel, Trinity, was available at the symposium book vending table. Lockhart was joined in conversation by Cherie Rivers, biodynamic farmer and UNC Chapel Hill, associate professor of geography and environment; and Jarvis McInnis, assistant professor of English at Duke University and author of Afterlives of the Plantation: Plotting Agrarian Futures in the Global Black South that was published a few weeks later. (For more about McInnis, see announcement below.)

Just as the legendary "Flower Ladies" of the South flourished through their bountiful gardens, the African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture symposium thrives thanks to a beautiful array of fiscal and in-kind supporters — organizations, institutions, and individuals:

Durham Library Foundation, Gardening Association of North Carolina, Durham Garden Forum, North Carolina Cooperative Extension Agency, Durham County Master Gardeners, Sarah P. Duke Gardens, New Hope Bird Alliance, North Carolina State University Libraries, Duke University Libraries, Preston Montague Landscape Architecture & Fine Art, Tributary Land Design & Build, Olli at Duke, Susan & Michael Hershfield. Other in-kind support was provided by the Hayti Heritage Center, Durham County Library and Morehead Manor Bed & Breakfast.

Centering African American Narrative Stories in Contemporary Environmental Literature and Media: Zelda Lockhart (modertor), Cherie Rivers farmer and UNC Chapel Hill professor; and Jarvis McInnis, Duke University professor.

Videos of the 2025 & 2024 symposiums

The African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium, 2025 - Panel 1 | Part 1The African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium, 2025 - Panel 2 | Part 2

The African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium, 2025 - Panel 3 | Part 3

2024 African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium

Young flower vendor, Durham NC. Photo: Jack Delano, May 1940. Library of Congress collection

Nefertti Goodman, Euphoria, water color and guache, 20 x 20 “

Abra Lee pruning rose bushes as a volunteer at the Georgia Governor’s Mansion.

Far right photo: Abra Lee’s horticulture students at Atlanta’s historic Oakland Cemetary.

Due to the exceptionally positive community response to the 2024 African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture symposium, planning team members Kavanah Anderson of Sarah B. Duke Gardens, David Michaud and Joanna Massey Lelekacs of the North Carolina Botanical Garden, and started to envision a follow-up event for 2025. Their goal was to make the next symposium even more widely attended and to secure additional sponsors and fiscal support.

The committee expanded by one to include Shakita Holloway, an exuberant young horticultural technician and native plant expert at the North Carolina Botanical Garden. Only a few botanical and public gardens nationwide employ African American horticulturists, so Holloway’s perspectives and experiences provided us with greater insights about shaping the 2025 symposium.

The second annual African American Legacy in Gardening and Horticulture Symposium took place March 28- 29, 2025 at the Hayti Heritage Center in Durham. Friday’s pre-symposium event was a free documentary screening of Jennifer MacArthur’s Family Tree. This poignant film takes a close look at black land ownership and sustainable forestry, and the challenges faced by two North Carolina families. Following the screening, audience members participated in a Q&A session led by Reylan Cook, a regenerative agronomy and food public policy advocate, with three of the people profiled in the film Alton Perry of the Roanoke Cooperative Sustainable Forestry and Land Retention Project, and Tyrone and Edna Williams owners of Fourtee Acres farm located in Enfield, NC.

Poster for Jennifer MacAruthur’s Family Tree documentary on black land ownership and sustainable forestry.

The 2025 symposium opened on Saturday with a lively West African jimbe and dundun drum dance processional led by members of the African American Dance Ensemble. During a dance tradition coming full circle, the dance troupe’s performance was applauded by the audience with hand clapping and dancing in the aisles of the Hayti Heritage Center performance hall.

View of the audience at the 2025 AALGH symposium

Deep bows and big bouquets to the 2025 AALGH symposium sponsors and supporters