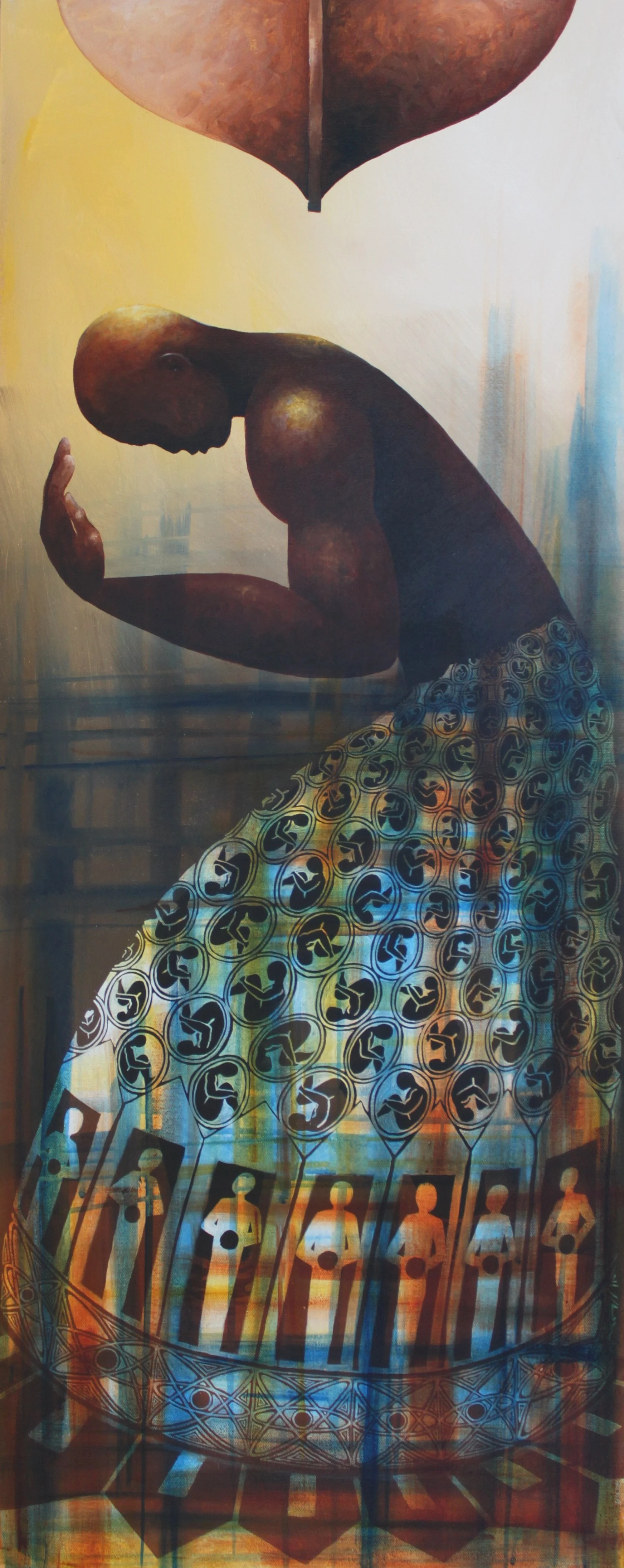

Natural patterns and human responses in Daniel Minter’s Universe of Freedom Making

Detail of Daniel Minter’s Universe of Freedom Making mural at the Smithsonian’s NMAAHC as one part of the two-part international exhibition In Slavery’s Wake: Making Black Freedom in the World which opened in December 2024 and traveled to the Museu Histórico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil for exhibition between November 2025 and March 2026.

A barely visible, porous, African profile etched in white and pointing left on the bottom of the woman’s red dress descends into ocean foam and bubbles into a weaving of spider spun webs and grass basketry woven by patterned hands.

On the left hand, a solid African profile with finger touching forehead faces a mask, all overlaid with vines.

A dead ash tree gains new being from its own barren limbs carved into beads.

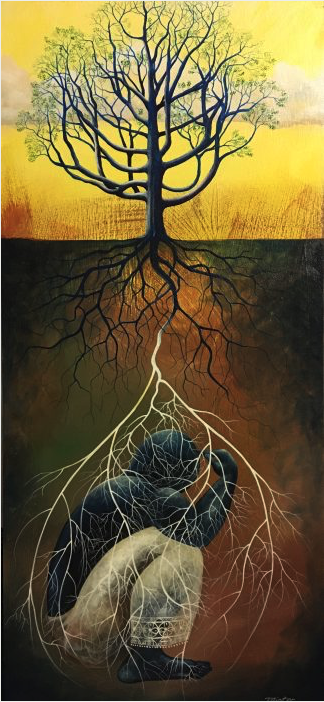

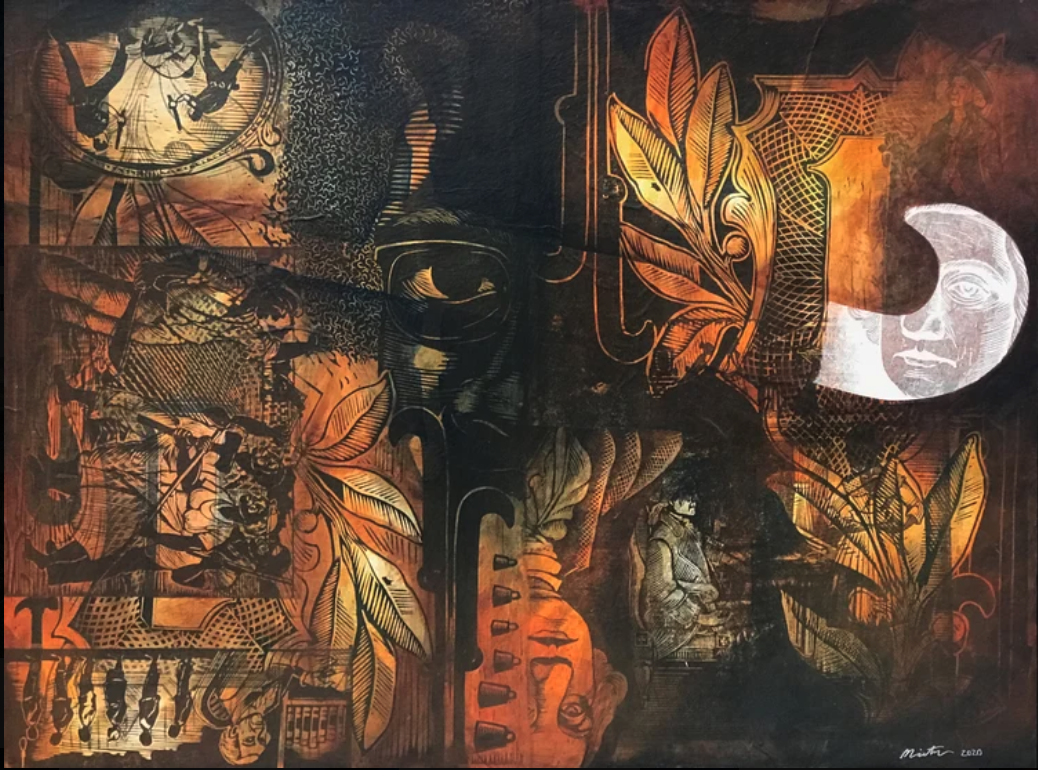

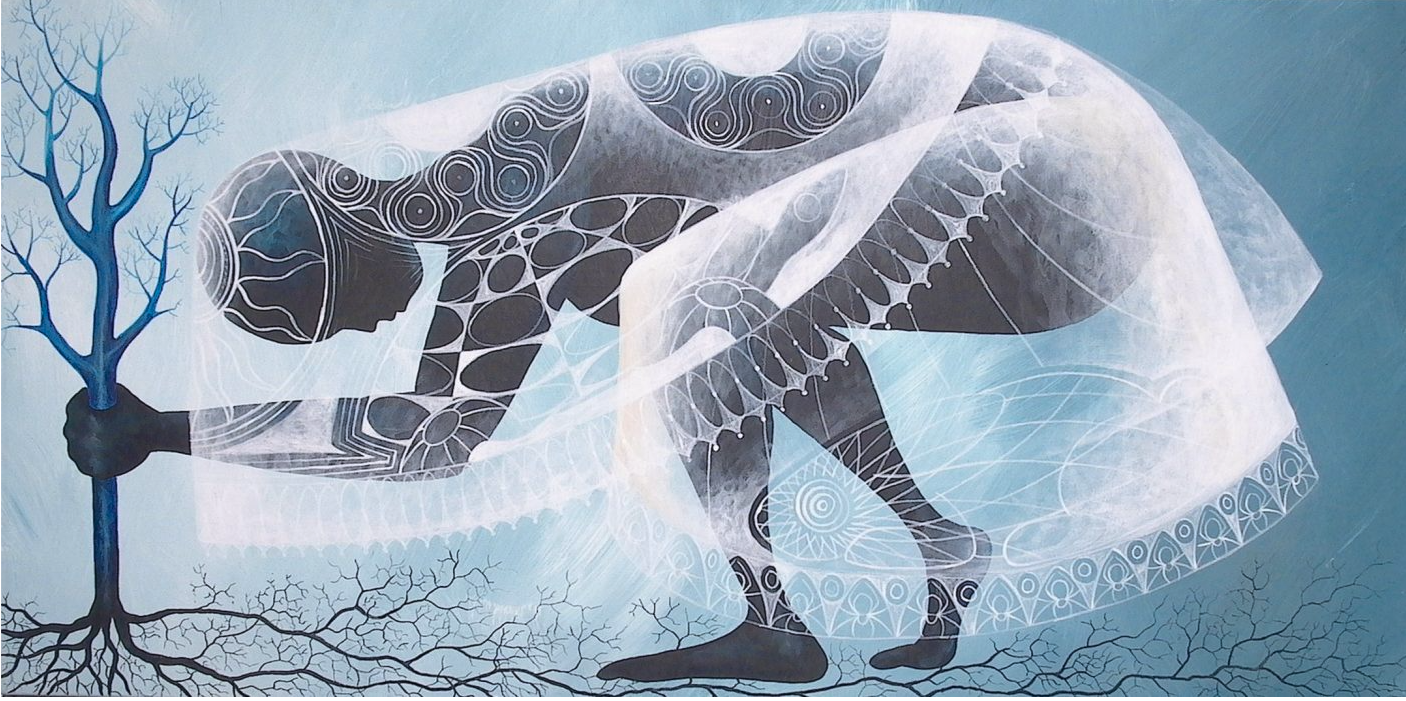

Daniel Minter’sHealing Language of Trees installation at the Lynden Sculpture Garden and an illustration from Minter’s 2023 exhibition, A Blue: Daniel Minter and the Layered Narrative of Illustration

Photos: courtesy of the artist.

“If the Earth does not have everything that you need

it will reclaim you and recycle you”

— Daniel Minter

Recycling and revelation are factors in Minter’s own creative reclamations.

Daniel Minter’s Healing Language of Trees installation at the Lynden Sculpture Garden, Milwaukee, WI.

Daniel Minter, Malaga Girl, Navigaton of Bones, acrylic from the “Othered Displaced from Malaga” series.

The tear-shaped bundle hanging from the woman’s dress is an nkisi made of gathered bones, representing ancestors buried in the Atlantic. Multiple works from the Malaga series contain minkisi (nkisi plural).

Nkisi is a Bantu word loosely meaning "to take care" and refers to spiritual objects that connect the living world with the spiritual realm.

Daniel Minter, A Troubled Water, 16 & 40”

Three dot proton detail from veil in Minter’s Hidden River painting. Minter’s painstakingly repetitive creation of fine details is like nature’s own recursive, fractal creation.

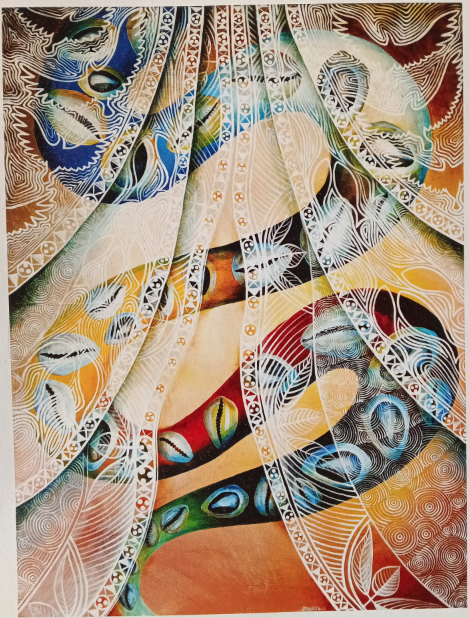

Daniel Minter, A Hidden River, 2011, 18 x 26”, acrylic, oil on wood panel.

Three layered veil with proton symbols

By 2011 when Hidden River (above) was painted, Minter was solidifying his lacy veiling style. The hidden aspects are the mystery he generates from iconizing familiar objects.

This painting was created to commemorate the 35th “Art and Survival” anniversary issue of the International Review of African American Art (IRAAA) founded by art historian Samella Lewis and now published by the Hampton University Museum. The 35 shells in the river commemorate that achievement and they also are embedded in a striking snake metaphor representing All-Seeing presence:

“The cowrie also represents clarity of vision spread along the river like the eyes on the back of the endless serpent of Oxumare.”

— Daniel Minter quote from foreword to the anniversary issue.

The anniversary issue coincided with a Hampton University fund raising campaign to support the treatment of patients needing financial aid for therapy at the university’s proton treatment center. In relating the Hidden River painting to the proton therapy, Minter said:

“A three layered veil of light opens to provide a glimpse of the hidden river. while each layer of the veil itself is edged by a pattern of circles that runs its full length,” Minter explains. “Enclosed by the circles in the veil are three dots representing the three quarks that form the proton.”

Daniel Minter leads installation procession at Lynden Sculpture Garden.

For Daniel Minter, the creative act is fundamentally one of revelation. In addition to being a visual artist, Minter is co-founder of a community arts organization with international affiliations.

During an interview about his Indigo Arts Alliance on the August 12, 2025 PBS News Hour, Minter emphasized that "the responsibility of an artist is to make the unseen seen” in a process that should involve the community. This vision, however, extends beyond the human realm and includes transhuman beings, both physical and spiritual including orixás (orishas).

This idea of encompassing the seen and the unseen was echoed by nature writer Samaa Abdurraquib, who at a Maine Coastal Botanical Garden interview with Minter three weeks earlier, began by thanking “all of the beings seen and unseen who made it possible for us to gather.”

For Minter, prominent transhuman beings include trees. "Trees move," Minter told me, not just meaning swaying branches. We were discussing his 2023 Healing Language of Trees installation at Milwaukee's Lynden Sculpture Garden, shortly before the debut of his In the Voice of Trees installation at the Coastal Maine Botanical Garden on July 27, 2025.

“Trees can make a lateral movement if there's an area that is closer to the water and they need to get there, he said. “They will send roots towards the water, and those roots will pull them slowly towards that area.” His explanation echoes a parallel phenomenon scientists observe as tree lines (particularly spruce and fir forests) gradually "march" into previously colder regions due to rising global temperatures.

This ability of the tree to adapt and shift its location mirrors Minter's own march across the Americas from his deep grounding in the earth of Ellaville, Georgia and art school in Atlanta to Seattle, Chicago, Salvador (Bahia), and New York City, before finally settling in Portland, Maine.

As Minter encountered a dead ash tree ravaged by insects, his impulse was to give it symbolic new life for the Lynden commission. The idea was rooted in his rural background. “I was reminded of the people I knew at home carving wood canes and that kind of thing,” he said.

The communal carving memory was his impetus for carving large beads from the limbs of the dead tree to “adorn it with the beads that come out of itself.”

He describes this process as “something before becoming something else again,” adding that “of course a tree is also a powerful symbol on its own.”

Self-sufficient community and craft

“You take out your pocket knife and you carve.”

“There were lots of people just sitting around for a few minutes,” Daniel Minter says, recalling wood carving in his rural home community in southern Georgia. “You take out your pocket knife and you carve. I knew one particular man who was a carpenter who would carve more intricate works but there was also a lot of relief carving. I feel like it originated with the Africans who came over and it's a southern black tradition—just carving on flat pieces of wood, whether that be decorating it or carving narrative imagery into it.”

Minter says his main focus is not the finished carving or installation itself, but rather the process and practice of creating it and connecting with people along the way. “That tree is a manifestation and representation of the effort and ideas that went into its creation. Without understanding the journey, it's just a tree.”

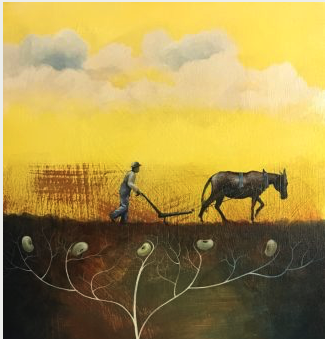

Daniel Minter, Inheritance I1, acrylic on wood, 12”x24”

Daniel Minter, In the Voice of Trees (Sticks in a bundle are unbreakable), Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, 2025.

“We plant ourselves wherever we are and we forever reach reach downwards so that we can nourish ourselves from the very center of this earth. So everywhere on this earth is our place, we belong everywhere.”

2 — Daniel Minter from 2023 talk at Bowdoin College

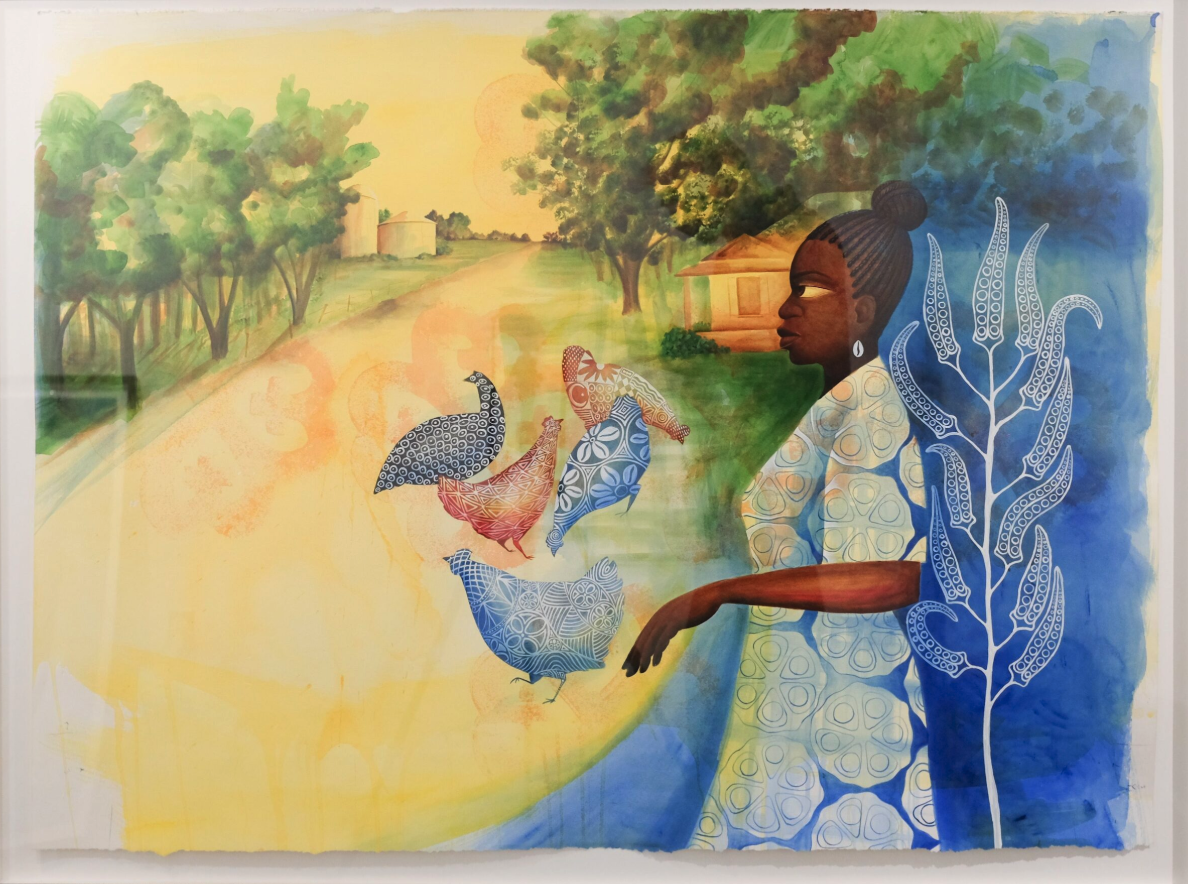

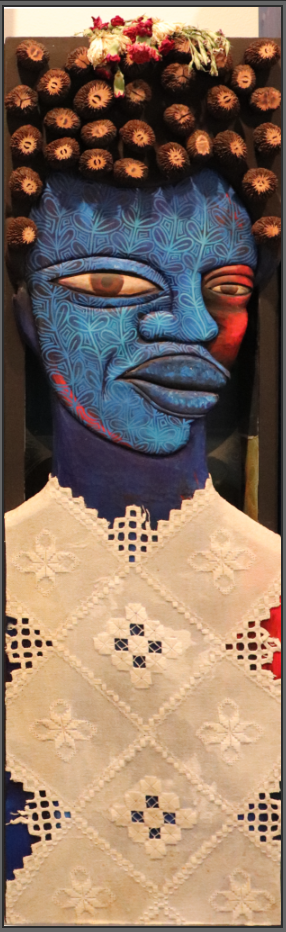

Reflections of Minter’s mother’s guinea fowl are decorated with adire cloth print patterns in this water color that combines West African and black Southern elements: indigo textile prints, cowries, okra, cornrows, guinea fowl and faint Adinkra patterns. The painting was on view in the A Blue exhibition of Minter’s illustrations for children’s books.

Minter today and detail from old stereoscope slide of black farmers in South Carolina. Like these men, Minter is seldom without his hat, an icon of southern agrarian life.

The lacy gossamer fabric veiling with botanical and marine iconography characterize a number of Daniel Minter paintings as exemplified by Minter’s Removal of Visible Presence for 100 Years (2011), part of his thematic series on the forced removal of a mixed-race community from Malaga Island, Maine, in 1911.

Marine (including chambered nautilus) and botanical patterns evolve into signature Minter motifs.

Nkisi bundle objects discovered in 2005 beneath the attic floorboards of the historic Wanton-Lyman-Hazard House in Newport, RI. The bundle is believed to have belonged to an enslaved man, Cardardo Wanton, in the late 18th century.

Photograph courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum/Joe Michael (am requesting photo repro permission )

Left: Indigo Arts Alliance (IAA) co-founder Marcia Minter whose whose orixá is Yemọja. In the Yoruba tradition, Yemoja is associated with the rivers. In the African diaspora, her domain expanded to include the vast ocean, representing her universal appeal as a nurturing forcce. She is a deeply protective and caring figure, offering comfort and cleansing to her children.

In addition to being a nurturing paragon, Marcia Minter is a seasoned professional. Formerly IAA executive director, she currently is IAA chief officer of strategic growth and innovation. Prior to establishing the nonprofit, Minter built a distinguished career as a corporate executive, serving for 16 years as vice president and creative director at L.L.Bean, where she oversaw brand identity and creative strategy across all channels. Her professional background also includes creative leadership roles for brands such as Microsoft, Nordstrom, and Essence Magazine. Strongly committed to social equity and cultural activism, Minter serves as a trustee for the Portland Museum of Art and a member of the Maine Arts Commission, and she holds an honorary doctorate from the Maine College of Art in recognition of her transformative impact on the region's creative economy.

Marcia Minter wears indigo-dyed cloth with the botanical pattern that is also used as the Alliance’s logo.

Indigo Arts Alliance logo

All photographs in this article are courtesy of the artist, unless otherwise noted.

For the Lyndon installation, Daniel Minter reached out to people in the local Milwaukee community to help carve the beads from chunks of the dead tree. He was capable of carving them all himself and would have finished sooner If he hadn’t put tremendous time and effort into organizing and conducting the carving workshop.

Daniel Minter has a quiet, reflective yet expansive personality that extends from solitary maker absorbed for hours in his large warehouse studio and contemplative loner drawn to forest trails to outgoing organizer who generously uses his energy and other resources to help other artists and communities through the influential Indigo Arts Alliance.

Minter's second tree project, In the Voice of Trees, at the Coastal Maine Botanical Garden, consists of seven cedar trunks stripped of their branches and bound together as a single entity. The trunks symbolize “Sticks in a bundle are unbreakable,” a West African proverb that speaks to the strength of social cohesion and cooperation in community life.

As in Milwaukee, the Maine tree project engaged the community in the creation of beads however in Maine the beads were molded from clay, another earth element, not carved from wood.

Detail from Daniel Minter, Inheritance I, acrylic on wood

12”x24”

Born in 1961, Daniel Minter’s early life was shaped by Jim Crow rule and spiritualized by the collective wisdom of his elders. His initial works, depictions of southern black farmers, were a direct reflection of his intent to project the people and environmental orientation of his past into the future.

Minter believes that his remote upbringing was a blessing, although he didn’t see it that way at the time. “I thought it set me back in a way, tying me to past generations and did not necessarily have anything to offer the future. Yet I was irrevocably connected to it.”

Even after moving to cities, Minter couldn't get away from his formative understanding of the world. “I was not willing to alter myself to something that was not of myself.”

And that understanding made him resistant to the self-centered aspirations and monetary motives of the establishment art world. “I know that the work I do benefits me practically and I know that the people where I'm from can read it and understand it and it does something for them as well.”

The Jim Crow system had made his people resilient. “That system we were forced to live under strengthened us in a lot of ways,” he reflects. The children and adolescents did well in school. “It gave us an appreciation for education because the education was coming from people you knew, people you trusted. It truly gave you the sense of who you could rely on.”

Close to the land, weeding by hand

Daniel Minter describes a childhood where the sustenance of the community came directly from the earth. “You grew a lot of your own food. My father had fields that were in different places and I worked on those. I also worked in the fields of other black farmers to help get their crops in. Picked peas, hoed leaves out of cotton and corn fields. And most of the weeding was done by hand.”

Weeding by hand! No herbicides. True agroecology before it acquired that fancy name.

This intimate connection with the land also shaped Minter’s understanding of the economy of resourcefulness. “There wouldn't be any surplus because if somebody had a bunch of corn, come harvest time, more than they needed, they would give a bushel of it to neighbors.” Their diet, consisting largely of seasonal produce, was exceptionally fresh and nutritious compared to the national “supermarket” chains that arose after WW 11 with large stocks of canned and packaged foods, and wilting iceberg lettuce and pale juiceless tomatoes in the small produce section.

“We always had a big food garden,” Minter says. “Almost everybody in the town had a plot in their yard where they grew lots of cucumbers or watermelons. And other people might grow lots of eggplants and tomatoes. The foods of the summer were different from the foods of the winter. In the summer, we had fresh cobblers, black-eyed peas, and butter beans—everything was fresh. And in the winter you'd have dried peas, and if you made a cobbler, it was gonna be from canned peaches. And folks had a yard hog that was slaughtered in the wintertime.”

“What about a cauldron?” I asked, imagining the big pots used to boil pork to remove the hairs. Minter was remembering another use of the big black kettle in the yard: “That's what my momma washed clothes in.” His mother had 12 children. Super woman! Minter associates his mother with Yemoja, who in Yoruba philosophy, is associated with motherhood, the sea, rivers and the moon..

As late as the 1960s, black rural women in the United States strenuously washed clothes this way, a detail that brings to mind John Biggers’s reverence for these women, as depicted with washboard, kettle and wringing cloth iconography in this lithograph and similar symbols in Biggers’ other depictions of southern black women.

Daniel Minter is the last generation to come out of the full traditional black southern culture that includes wood carving. When he was growing up in the 1960s, “it was more like the 1940s or ‘30s” there, he says. Now Minter is an energetic culture-carrier and preservationist of old traditions.

“Even simple actions, like sweeping our front yards with a brush broom – something I thought was just a common chore growing up – are very connected to the (African) continent.

My mother's passion for Guinea fowl, too. I've grown to see the connections there. My mother preferred guinea fowl over chickens because of their habits, their appearance, and the sounds they made. I later learned that the guinea fowl was also the food for Yemoja. I strongly relate those ideas of mothering, which I feel my mother exemplified, to the orixá Yemoja.”

Citing a painting from his black agrarian works, Inheritance 1 (shown above), Minter says, “It’s about the harvest of all that our ancestors have put into this land.”

Orishas, natural symbols and signs (ecospirituality)

in the southern African American tradition

Rachel Harding’s father is historian Vincent Harding, co-founder of the pathbreaking Institute of the Black World.

In There is a River, Vincent Harding described orisha-like manifestations in the southern African American sensibility. Daniel Minter says he sensed such spirits when he was growing up in Georgia: “I felt connected to the spirits and the force of the field but I did not have a name for them.”

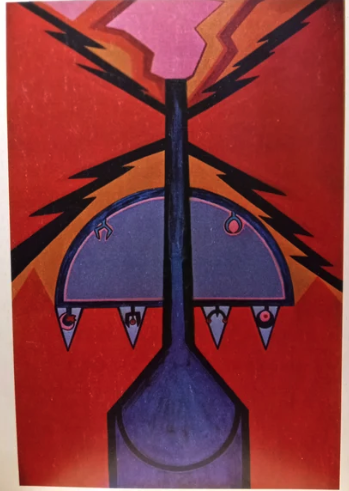

Here’s Vincent Harding’s description of Nat Turner’s spiritual world:

Turner knew that he had only one real master, the one “who spoke in thunder and lightening and through the swaying leafy trees,” and he closely observed signs in the natural world. The sign for rebellion came in February 1831 with an eclipse of the sun. The second sign came on August 13, 1831 when the sun appeared bluish green.

Green trees a bending

Poor sinner stands a tremblin’

The trumpet sounds within-a my soul

I ain’t got long to stay here

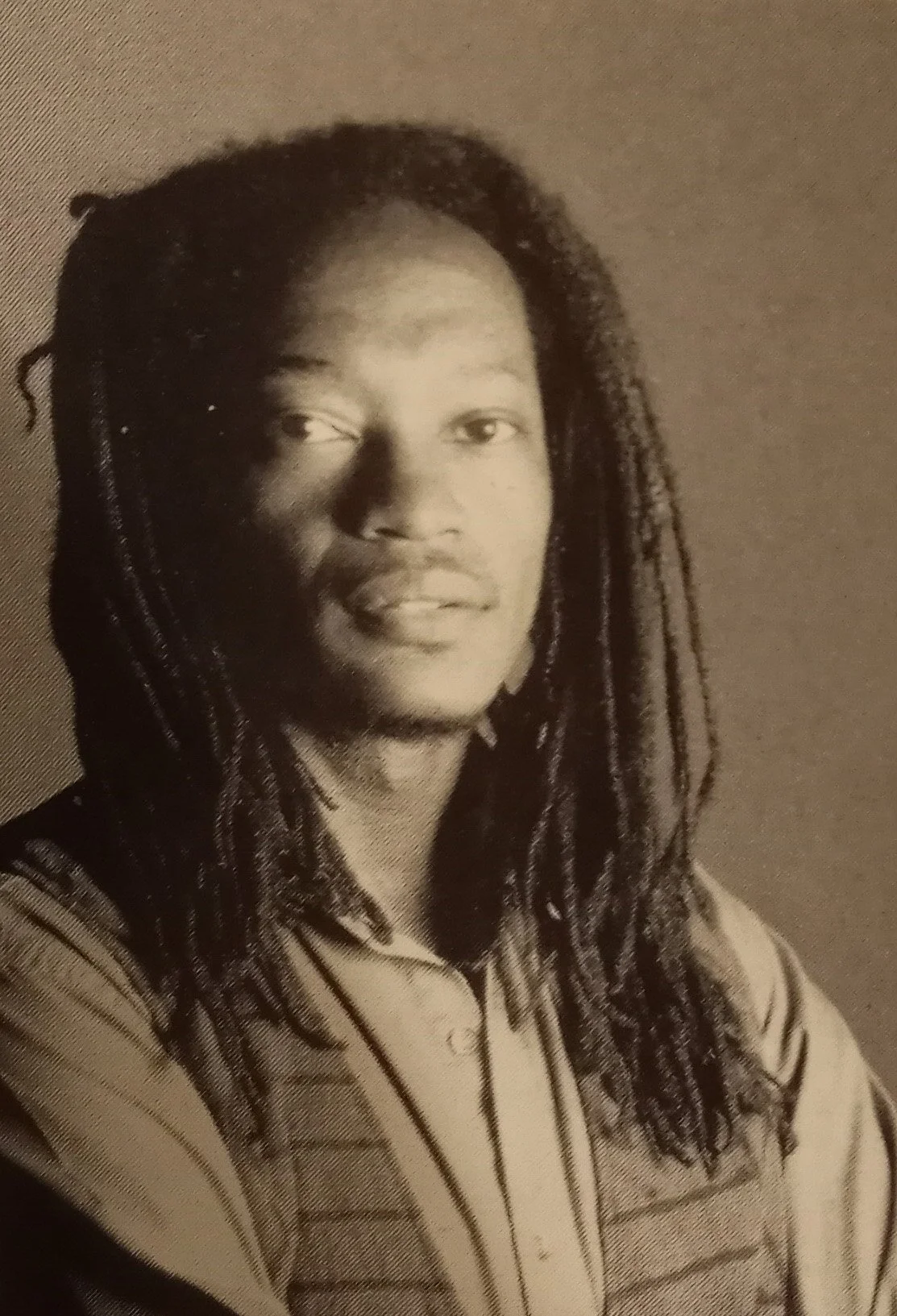

Daniel Minter, 1997.

Daniel Minter, A Distant Holla, Currency Exchange, mixed media sculpture installation

60”x45”

Private Collection of the Portland Museum of Art

The gossamer veil is a layer that indicates “the presence, or the embodiment of spirit, and the ability to exist in that realm and this one at the same time,” Minter explains and credits his conversations with both John Biggers and Leo Tanguma, a Mexican American muralist, with helping him understand this concept. “The three of us were trying to incorporate the spiritual realm but using figures that were the kind of people we all three grew up with—rural people who were connected to the land but in a way that, even if they were in servitude, they would find a way for the land to serve them as well… . Biggers showed that spiritual presence is close by, just on the other side. He would create these patterns that slowly revealed another image or a different attitude within the work. He used that on the clothing of his figures as well. It connects to the concept of the Mother.” (Scroll all of the way down this Hampton University page for close up views of Biggers’ veiling technique.)

Being attuned to nature in a very deep way

The veiling⇆revealing technique also relates to his use of the color black. “One of the primary reasons is the determination to be present as myself,” Minter says. He works with the “full spectrum of that blackness—from the deepest blacks of deep space to the deepest blues of the bottom of the ocean.” By doing so, he encourages viewers to look beyond the surface and interpret the other things within the work. “The voice speaking, it is a black voice,” he says, “and it's one that resonates with the universe.”

While Daniel Minter finds personal and universal resonance in the "full spectrum of blackness," his connection to these concepts was formalized during his time in Bahia, Brazil, where he was introduced to Candomblé, the Yoruba-based spiritual system of the orixás.

“It's about working out understanding based on numbers and patterns,” he says. “It helps me to recognize the unseen influences on what's in front of me—whether those influences are beside it, below it, or above it. The more of these connections you see, the clearer your understanding becomes. These relations aren't always visible, but we constantly encounter unseen influences. For example, the traffic you don't see influences your progress when driving to work. These invisible influences are powerful ways of helping us understand the whole paradigm.”

Minter was influenced by such spirits growing up in Georgia:

“But I did not have a name for them. I felt connected to the spirits and the force of the field but I did not have a name for them until I got to Salvador (in Bahia, Brazil).” He learned about them first through conversations with artists who would give him a name for the spirit connected to a piece of art. “That’s where I became familiar with Candomblé and the amount of organization of those ideas around the spirit that exists within the living world.”

“How did you sense those spirits when you were in Georgia?”

“By the way I was drawn to, and am still drawn to, any grouping of trees or forest,” Minter replies. “I want to go there and I always feel a sense of presence. It’s a place where it's easy for me to connect to being a part of existence and not a part of someone else's 'mechanism'.”

When Europeans discovered that enslaved Africans believed in orishas, they “thought that that was a part of being the devil,” Minter explains. “But actually it's a way of being attuned to nature in a very deep way. And needing a way to express it in a metaphorical way that’s also very real in terms of what it represents.”

Another major environmental element in Minter's life and work is the indigo plant. His journey with indigo began long before he consciously embraced it, steeped in the very soil of his regional, South Carolina-Georgia homeland where indigo was cultivated before the advent of commercial dyes. Many enslaved Africans brought with them extensive knowledge and expertise in indigo cultivation and processing from their homelands. Some were so valued for their skills that they were called "indigo slaves."

When Daniel and Marcia Minter co-founded and named the Indigo Arts Alliance (IAA), they chose the botanical name for its beauty, historical significance, and its ability to represent a heritage shared by Africans and southern African Americans.

The indigo plant is also represented by Minter’s illustrations for Blue: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky, a young readers’ book by Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond.

Reflecting on motivation to found IAA, Minter says “I realized that the work artists do requires other artists — those with similar sensibilities, aesthetics, or a similar care for their community — to serve it in some way and having a place to create and talk about the work.”

If the Earth does not have everything that you need, it will reclaim you and recycle you

After Minter left Georgia, he lived and worked in Seattle where he met and married a graphic designer. Marcia and Daniel moved to New York City. Then, finally they settled in New England by the water – the archipelago of Portland that has lots of inlets.

I wondered whether after moving to Portland, the water themes became more prominent and the environmental themes expanded in Minter’s multi-media works.

“I think that they are probably more prominent for two reasons,” Minter says. “I'm really interested in connecting the real life I have to the rural life that I had in Georgia. In both, I nourish myself from the earth. The communities are vastly different, but the earth is the same. Wherever you go, the earth has everything you need. If it does not have everything that you need, it will reclaim you and recycle you.”

The move to Portland and his deeper understanding of the orixá Yemọja, the mother of the water and ocean, have also influenced his work. “It also helped me understand something about myself: I am not comfortable in water. I don't swim, and I've never liked swimming,” he says, true to his upbringing in a rural, low per capita income, landlocked area.

He then recounts a dream in which he and Marcia, whose orixá is Yemọja, helped him fly over water. “I feel like it just gave me an understanding that I needed Yemọja's permission before crossing the ocean.”

Minter also notes that his orixá is Ogun and later returns to the topic: Ogun. “He is one of the spirits of the forest, specifically the spirit of opening paths through the forest, creating new routes, and of farming fields. He's also associated with tools, particularly metal tools like wood-cutting tools, and the general development of material, primarily iron. These energies were incorporated into the energies of the orixá Ogun for the benefit of civilization, for us as people.

Knowing this gives clarity to many of the reasons behind the ways that I think—the way that I do. Not that it gives them justification, but it does provide a little clarity. It's knowing that there is a system of thinking that's thousands of years old, which has been contemplating how we live in the world and how our different personalities and energies can be used to make a whole community in this world.”

Marine scenes and aquatic motifs— symbolic boat imagery, Malaga Island figures evoking Yoruban figures who govern waters, and cowries and other shells—constitute an African-influenced, marine sensibility in his work. Maine’s Malaga Island was once home to a mixed-race community, including many African Americans, from the mid-1800s until they were forcibly removed in 1912.

Minter is working on a book that features his work in dialogue with the work of comparative religion scholar Rachel Elizabeth Harding. At one point during their long, cross-fertilizing collaboration and friendship, Harding wrote that Minter is concerned about “the commodification of Black bodies and Black productivity at the founding of the modern world – and how slavery, and the persistence of Black fungibility has provided the reigning paradigm for capitalism into the 21st century; using up everything and everybody until there is nothing left. And then using the carcass.”

Harding added that Minter’s magical methods reveal “those vital, transformative modes of being, that are cultivated over generations and that carry an-other meaning of the possible (an afrofuturist vision) at their heart. Minter’s art is the labor of tender excavation, unearthing the wisdom buried in the culture – sometimes deep in the terrain of memory, sometimes flat-footed in plain sight all around us.” ( Quote from “Quantum Exchange: The Diasporic Art of Daniel Minter” by Rachel Harding in Rethinking Marxism, 33:1, pp. 30-51 (2021).

The Minter-Harding co-authored book, he says, “encompasses all the themes we've highlighted in our collaborative journey over the years. It involves discussing the work, her writings, and pairing pieces together to create a walk-through of our collaboration.”

Another project involves illustrating themes they have discussed. “I've realized that within my work, there are consistent elements: the human body or figure, which I often use as a metaphor; the representation of spirit through color and line; and the use of metaphor,” says Minter.

When I pointed out the repetition of the word “metaphor,” Minter clarified: “I think of the ways in which we expand on the metaphor outside of the piece of work that generates it. How one metaphor can lead to another. Similar to the way the removal of the black and mixed-race families on Malaga Island here is a macrocosm of the removal and destruction of black communities all over the South during that same period. The metaphor can expand to talk about what was going on in the whole country at that time.”

Daniel Minter created the cover art for Rachel Minter’s A Refuge in Thunder book based on her PhD research on how Bahian Candomble practices were a lifeline and shield against psychological and cultural extinction.

Souls grown deep like the river

There is a resonance between Minter’s Hidden River and Xango and Ogun by Abdias do Nascimento (shown above right).

In The Hidden River painting, Minter evokes the spirit of Ogun, orixá of metalworking and technology, to symbolize the university's science and technology capacities, along with the endless river serpent, Oxumare.

The Hidden River evocation echoes singer Dianne Reeves’ powerful invocation of the energies of southern African American orixás (“old souls”) on this video . The following lyrics about a child who fell to earth from a crack of lightening are excerpted from her song:

“…Consecrated earth it was a sacred place

A perfect balance of nature a gift to all the world

Still I throw away the oyster just to wear the pearl

In my darkest deep depression

They give counsel to my soul

They open up new meaning

And God's power takes control....”

Songwriters: Dianne Reeves / Eduardo Del Barrio

In Minter’s renderings, orixás “open up new meaning.”

Lacy gossamer detail from Minter’s work. (See full examples below.)

Daniel Minter remembers his mother washing clothes in a kettle like the one shown here.

Woman and child in North Carolina, 190l.

Photo in U.S Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

Minter’s style of painting evolved to incorporate a gossamer element: white outlines of botanical, aquatic, and animal motifs—for example, lacy filigree leaves, vines, and frogs. “I don't really have a name for it—sometimes I'll call it a veil,” says Minter. “I started doing that out of two reasons: conversations with John Biggers and also spending time in Salvador, Bahia.”

Abdias do Nascimento, Xango and Ogun (grantors of technology), arcylic, no date (before 1977).

Photo reproduced from a 1977 issue of Black Art: an international quarterly published by Samella Lewis.

“Sticks in a bundle are unbreakable” West African proverb about the power of being together

Seven tree trunks bound are one in Daniel Minter’s In the Voice of Trees representing the “Sticks are unbreakable proverb” in a 2025 installation at the Coastal Maine Botanical Garden. Minter’s beliefs and experiences are reflected in the collaboration between Indigo Arts Alliance based in Portland and the Botanical Gardens in Boothbay, Maine.

The two organizations developed a three-year partnership to convene the Deconstructing the Boundaries symposia to bring together “community members of all backgrounds to ground ourselves in difficult conversations, creative expression and the power of being together.”

Loss of the integral West African wood carving tradition

During our conversation, I lamented the loss of the African American wood carving tradition. I was reminded of the stool from Ghana intricately carved into interlocking forms from a single block of wood in my front room and another form of masterful carving by Benjamin Banneker. Around 1753 Banneker constructed a clock made almost entirely of wood. He scaled the hand-carved wooden gears and cogs based on his own drawings and calculations. Benjamin's paternal grandfather, Bannka, who was captured in West Africa and had been enslaved, possibly taught his son and/or grandson the highly skilled carving craft.

After recalling wood carving among his southern father’s generation, Minter says of the current generation:

“We don't have the time … and the joy. We’re disconnecting ourselves from our understanding of the physical world by turning to the digital world. That's a form of control, when we’re not responding to our own natural surroundings but when we’re controlled by the media, and the media is controlled by corporations. They want our energy and our labor to run their machines.”

The porous lace tracery of Minter’s figures allows them to mesh into one another

The figures in Quantum Exchange (particularly in the right panel of the triptych) suggest that porosity reflects the dominant emptiness of form. Physical matter is nearly all empty space (around 99.9999999%), because atoms are mostly void, with tiny nuclei and orbiting electrons.

Minter’s wholly transformative dream

“… But sometimes, as in the painting Minter calls quantum exchange, the lines are not simply embellishments; they become the thing itself and offer the viewer a way of seeing the subject of the piece from an entirely different visceral experience; an experience of embodiment. This painting relates to a powerful dream Daniel had in his twenties, in which he was transported and transformed into an essential element of the life force, like an atom or quark. In that infinitesimal state, he moved through many forms of matter – trees, plants, birds, insects, even human remains and the deep soil of the earth. And in each instance Minter became everything he passed through, everything he encountered. At the center of the earth, in the dream, Minter met an ancestral presence who was, at the same time, the artist himself and who lamented the continued enslavement (to capitalism, racism, alienation) that Black people, and all human beings, suffer… .” Excerpt from Rachel Harding’s September 2019 essay, Quantum Exchange: The Diasporic Art of Daniel Minter

Dissolution of boundary between subject and object

Referring to the Quantum Exchange triptych in a talk at Bowdoin College in 2023, Daniel Minter explains the psychological alchemy that transports him to a base level of reality:

“ In one panel, there is a young man dancing; I am looking into the act of connecting with the world through our bodies—using your physical presence to connect to a spiritual world, which is depicted in the second panel. In making that connection to the spiritual world, we use all the other things that exist in this world to understand it. Once we have made those connections, we are able to place ourselves in that realm where there are no physical bodies and no separation between the things that exist in this world and ourselves.

Daniel Minter, Quantum Exchange (insert medium & date)

Rachel Harding and Daniel Minter collaborated on the conception of Minter’s Water Road series right after Hurricane Isabel. “We were both thinking about how, in that situation, every direction was water,” says Minter. “There was no way to get to any place without traveling through that water — it was like a road.”

A universe of freedom making

Daniel Minter’s work will always be a unified expression of his core life background and beliefs. This is a “universe of freedom-making” that, as Minter says, “lives within us, within our DNA. Even in challenging situations, we can still cultivate our freedom. Even if our bodies are chained, we have the capacity to cultivate freedom within ourselves, and we seize an opportunity to do that every time we're able to connect with our source material, which is the earth.”

The “universe of freedom-making” specifically refers to the title of Minter’s current exhibition. Presented by the National Museum of African American History & Culture in DC, a Universe of Freedom Making is one part of the two-part international exhibition In Slavery’s Wake: Making Black Freedom in the World which opened at NAAAHC in December 2024 and travels to the Museu Histórico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil for exhibition between November 2025 and March 2026.

“... gathering momentum in the same direction of freedom”

This spiritual wellspring is an indigenous way of comprehending the world that, as Minter says, “is also about a black and indigenous attitude of generosity and welcome.”

The traditions—West African, Bahian, indigenous North American—are distinctive but also very complementary. Both can happen at the same time: difference and union. On the black and brown tip, Minter begins by recalling his childhood.

When I grew up, we did not have strong connections to the indigenous community, though one of my aunts was indigenous. My uncle married a woman from, I think, North Carolina. She was indigenous, and we used to love talking to her because her name was so long. We tried to remember her whole name but we just called her Aunt Ken.

I say that to say there has always been an underlying relationship but it's been difficult because we were striving for assimilation and they were also striving for assimilation. We were resisting slavery and subjugation and they were resisting colonization. Those forces were acting on our relationships with each other, so it's been fraught. However, when those external forces were put aside, there was generally a connection.

I didn't truly experience this until the welcome table event in Denver with Rachel Harding and the Veterans of Hope. They held a community symposium and a gathering of black and indigenous communities, which was a wonderful event where black, indigenous, Latino, and white communities talked and gathered momentum in the same direction of freedom.

When I moved to Maine, I learned that there's a large Indigenous community here but there was very little visibility of them, much less than out West. I felt they were a strong community and wanted to do more with them. So, I've really wanted to include black and indigenous ideas and aesthetics within Indigo's mission and ideology. We host indigenous artists from this area.

Until being here, during a welcoming ceremony performed by an indigenous artist, I had never truly felt welcomed to walk on this land. They have a welcoming song they sing; they call themselves the People of the Dawn—the people who the light hits first when it comes over the water. This is beautiful because the land here jets out into the ocean and gets daylight first. And when people come down the river or on the ocean, they welcome them with that song. We've had that song sung for us a few times, and I must say, it was the first time I felt welcome.”

Going against what inherently wants to be

In our a wide-ranging exchange about cultural and environmental ecologies, we agree that it's the Trump regime’s loss not to understand that unity-in-diversity and inclusivity are humanity’s wealth — the real wealth.

Minter says that the MAGA governing forces are acting in an authoritarian way because they do not understand this concept of wealth: “This is all about control and they will continue to lose control because they're going against what inherently wants to be.”

Getting into the time space of trees

Minter’s beliefs and experiences are reflected in the collaboration between Indigo Arts Alliance based in Portland and the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens in Boothbay, Maine.

The two organizations developed a three-year partnership to convene the Deconstructing the Boundaries symposia to bring together “community members of all backgrounds to ground ourselves in difficult conversations, creative expression and the power of being together.”

Minter’s “In the Voice of Trees” installation was an integral part of the third year Deconstructing the Boundaries symposium held on July 27, 2025. During an interview at the symposium, Daniel Minter continued to preach the gospel of trees.

“Trees stand erect like people but have far longer lives, grow more slowly than we grow and have ‘seen’ more than us and so have a different relation to time than we do. I would like for us to be able to see that and find a way to get into that time space.” — Daniel Minter

Daniel Minter, Water Road series

For Harding’s full interpretation of the series, see: “Water Trouble: The Road, the Boat and the Third Thing”

Indigenous Artists in Residence at Indigo Arts Alliance:

Gabriel Frey (Passamaquoddy); Jeremy Frey (Passamaquoddy), Anna Tsouhlarakis (Navajo / Creek / Greek), Shane Perley-Dutcher (Wolastoqiyik / Maliseet)

In addition to individual residencies, Indigo Arts Alliance organizes programs that bring together cohorts of Indigenous artists for collaboration and dialogue. These include Re/Union: Re-Editioning Black + Native Histories (2022), a major gathering organized by IAA at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts for Black and Indigenous artists to "re-edition" history and share knowledge.

Participants in Re/Union: Re-Editioning Black + Native Histories (2022) at Haystack. Photo: Sofia Aldinio

Woodlands view of Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, Boothbay ME. Photo courtesy of CMBC

Detail from “A Universe of Freedom Making” at the Smithsonian NMAAHC. Photo: Maansi Srivastava for The New York Times via Daniel Minter’s representive Greenhut Gallery.

Levitating figure

Boat prow

Submerged figure

Curved fetal form

Bare branches, roots, lacey tracings

Levitating figures, variation of the “holding” motif

Work tools are also a repeating motif as seen in A Quiet Reach 1.

A Quiet Reach 5 brims with other familiar motifs including nkisi buttons.

Both works are in the collection of the Portland Museum of Art, Maine.

View them here

In a Quiet Reach 1, note how the arms are folded across the chest with fisted tools in the style of the Wukanda salute from Marvel's Black Panther: crossed arms over chest in an 'X' shape, a symbol Inspired by Egyptian pharaohs and West African sculpture.

Levitating figure: “That figure is bound, boxed for transport.” — Daniel Minter (D.M.)

Boat prow: middle passage, also womb. “A heavy vessel of our journey. The symbol of so much cargo, so much loss, and weight. It looms very large in our history.” — D.M.

Calipher: “Used to support racist, eugenic arguments. But it does have a subsidiary interpretation: some see forceps as well. That’s why the symbology is open.” — D.M.

Bare trees: branching limbs connected to branching roots, living arteries, death

Subverting “burr head” epithet into a striking reflection of nature’s sculptural beauty.

Blue black skin

Gathered here are the exiled silhouettes of Malaga Island, Maine; the wide-eyed/squint-eyed faces of Ellaville; the iawos and orixás of Candomblé; and the ordinary tools of an older, yet present, Southern Blackness – kitchen combs, nails, sideways glances, stacy adams by the barbed-wire fence, big bones and farming tools, rocking chairs and the bare black arms of trees.

— Rachel Harding referring to Daniel Minter’s 2011 Hammonds House retrospective exhibit

Left: okra detail from Minter’s Quantum Exchange

Right: photo of okra cross-section from Wikimedia commons.

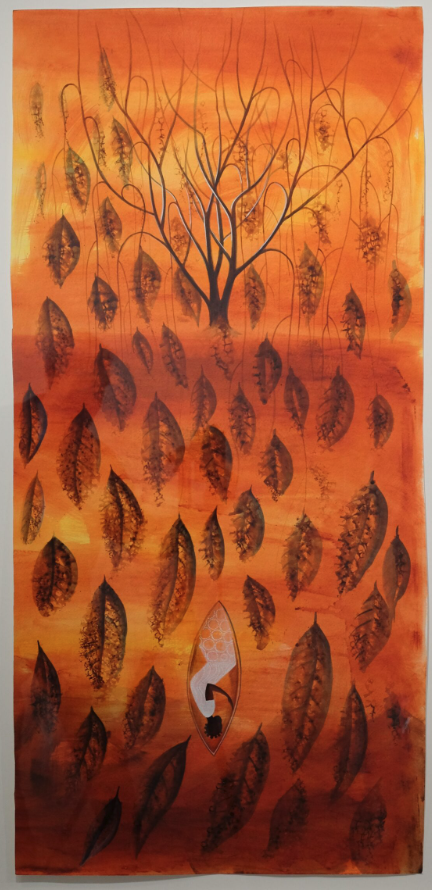

Bare branches. Leaves disintegrating into loam, rich nutrient for seed of an African female archetype to grow in the New World womb.

Faint adinkra pattern with cotton boll tracings

Repeating agrarian theme

Holding what can not be taken away.

Detail from Malaga series.

Interface of human and other life forms. Botanical-patterned skin.

Detail from A Quiet Reach (see full image and art work details below).

Relatives across the waters

Minter’s recurring motifs

Currency motif from “States of … 5,” series, collage print and acrylic on panel.

“The weight of living in a society that has used black people as currency.” — D.M.

bare branches

journeying

Boat prow

Calipher

Skin imprinted with botanical patterns.

Veiling and revealing qualities of lacy patterns.

Archetypal West African profile. Minter recognizes the original people with that profile and those who’ve propagated it in the Americas.

Relatives across the waters.

On John Biggers’ veiling technique and impact:

“He was communicating with the same basic community that I was trying to communicate with. Ane he showed me it's possible to communicate with a small community in South Georgia and at the same time communicate with one that's in Ghana or Harlem.” — D.M.

“I really enjoy looking at trees in winter while they are sleeping. When they are resting, you can actually see "who" the tree is. You can see its language—the way it branches and the patterns it forms. I enjoy seeing the structure. If I add leaves, I try to be very spare with them.” — D.M.

As we finalized the prep for this article, I talked with Daniel Minter for one last conversation. We spoke on January 16, 2026, a day that felt heavy with the current political climate, yet Daniel spoke with the grounded perspective of a philosopher who looks through the surface of things to find the underlying structure.

Our discussion began with a concept Minter has been meditating on for some time: "the weight of living in a society that has used black people as currency."

If you don't understand what that weight is, you can easily mistake it for something lacking within yourself—some inefficiency in your own psyche or body. But really, it is a weight from that history.

The other thing about that weight that fascinates me is that while most Black people understand it, white people carry that weight, too. They have no idea they are carrying it, but they are. It causes them to act in insane ways, and they don't understand why. But it is that weight they carry, just as we carry it.

J.H.: Yeah, and there is the weight of the entire colonial enterprise on the original people here. They have to carry that weight, too.

D.M.: And when Africans arrive here—say, from Senegal, Nigeria, or Zimbabwe—they don't initially have that weight. But they acquire it after being here and they often have a difficult time understanding it. When they first get here, they feel as though they just walked into a land of freedom.

J.H. A very good example of that now is the Somalis living in Lewiston, Maine. Trump is headed for them now. This is a terrifying time but the artist has so much to contribute.

D.M: I try to talk about it using metaphors that are not necessarily locked into, or reflective of, one particular point in time or a particular event, but of a system and a pattern of things. Whether you lived through Jim Crow or are living through this current era, the metaphor still fits… .

I realize now that I really enjoy looking at trees in winter while they are sleeping. When they are resting, you can actually see "who" the tree is. You can see its language—the way it branches and the patterns it forms. I enjoy seeing the structure. If I add leaves, I try to be very spare with them.

J.H.: There is also a complementarity between the branching aspect of tree limbs, the branching of roots, and things like rivers. Branching is a basic pattern that nature creates. Rivers branch into tributaries and creeks. It’s an earth pattern, like the lace, like snow flakes.

D. M: I started doing that (lace veiling) when I was painting in Brazil. There is so much lace within the clothing people wear in Candomblé. There’s also the strong idea of a layer between one world and another. I started using it to represent the spiritual world.

I also had conversations with John Biggers about showing that spiritual presence—showing that it is close by, just on the other side. He would create these patterns that slowly revealed another image or a different attitude within the work. He used that on the clothing of his figures as well. It connects to the concept of the Mother. So, I started using that to show that presence in my own work.

J.H.: I have seen a photograph of people in Brazil showing a man with a mask made of beads. You can see through the beads, but it is still a veil.

D.M.: Right. They put that on when they are embodied with the spirit. When they have the spirit of the Orisha, they use that veil because they are no longer the person you see; they are representing that spirit.

J.H.: If our so-called democracy can survive and grow toward fulfilling its promise, we are going to have to think in new ways. Some of the ways we need to think are just not available to even well-intentioned people because they don't acknowledge our ancestors and their spirituality. How was your trip to West Africa?

D.M.: All of the things we’ve been talking about were present. I had never been to Nigeria before. I’d gone to East Africa—Kenya, Tanzania, and Zanzibar—in 2015, but I wasn't really interested in going to West Africa initially. I was more interested in the Diaspora—Brazil and the Caribbean. Africa felt a little too direct. I felt like I didn't know who I was, and I couldn't go there to find myself if I didn't have a sense of what I had, myself. By getting familiar with the Diaspora, I realized how much we have maintained and how beneficial those things have been.

When I finally went to Nigeria, I felt affirmed. I was able to see how I fit into the cosmology of the Diaspora and the Mother.

Nigeria is so complex. There are so many groups of people with varying belief systems and cultures. The Yoruba and the Igbo, for example: those small differences to us mean a lot there. Here, those differences were merged because we are combinations of both. We had to figure out the valuable parts to keep from each group.

We kept parts from so many different people that we cannot say we are just from Ghana or Fulani. We know our influences are much wider than that. We have to be prepared to claim it all, because we survived using it all.

J.H.: That is a good point. Do you sense this understanding beginning to germinate in your work?

D.M: The thing I’ve been thinking about is that in Nigeria, and Africa in general, there are so many systems for recording information. So much credit is given to written language in the West, but there you realize information is transmitted through dance, music, intonation, symbols, and patterns. All of that is valid information passed down through generations.

J.H.: And we used pieces of those systems here, but we don't necessarily acknowledge them because we are so tied to the written word.

D.M.: Exactly. If it isn't the written word – letters and numbers – it is often not considered information. That is why I try to use symbolic objects and repeating patterns in my work—to help people interpret the ideas without relying solely on text or literal objects.

We closed our conversation by discussing his exhibition, Universe of Freedom Making which was closing soon in Brazil. It is a testament to the tools our ancestors gave us — the ways we use our bodies, our voices, and our language to maintain ourselves.

Daniel Minter spoke and continues to speak about how black people have manipulated these survival techniques, reorganizing them over generations. These systems of freedom making are a reminder that no matter our physical condition or location, we have always possessed the means to retain psychological and spiritual freedoms.

section under construction

Will insert:

Minter photos from Nigerian trip

electronic installation that Azari and Daniel created for A Universe of Freedom Making.

Indigo Arts Alliance, 60 Cove St, Portland, ME 04101

Daniel and Marcia Minter built this facility up from the ground.

And still IAA rises!

Indigo Arts Alliance executive director Jordia Benjamin explains how the organization is continuing to fulfill its mission during these precarious times for non-profits.

While the last year presented serious challenges, including funding instability and external pressures on cultural institutions, we addressed them through strong partnerships, community trust, and donor support. No essential programs were cut. Instead, we emerged more focused, more resilient, and more influential, proud of our ability to protect space for Black and Brown artists to have their voices heard and their visions nurtured. Since we opened our doors we've hosted 85 artists in residence via three artist-in-residence programs. These artists represented 22 countries across the African diaspora, spanning disciplines such as poetry, textiles, visual arts, performance arts, and ancestral storytelling. Last year we either hosted or co-hosted 68 programs in partnership with 39 organizations, welcoming 2,530 people to in-person programs and engaging more than 140,000 people digitally across 377 cities worldwide.

For more information about the Alliance and how to support it, visit: https://indigoartsalliance.me/