The Mississippi river flows through Malaika Favorite

Two moments, same afternoon:

On Friday, July 4, 2025, during a White House ceremony held sometime between 4 pm and 6 pm (the public record of the exact time is not clear), Donald Trump signed his self-proclaimed “big, beautiful” bill into law. This legislation slashed allocations to insurance and nutrition programs that serve vulnerable Americans to facilitate more substantial tax reductions for high-net-worth individuals and corporations. It also decreased funding for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) which directly benefits fossil fuel corporations by lessening regulatory oversight and enforcement costs. Trump foreshadowed the EPA cuts at his January 2025 inauguration when he gleefully chanted, “Drill, Baby, Drill!”

On Friday, July 4, 2025, at 5:45 pm, Malaika Favorite texted me a copy of a 1991 article about her father, Amos Favorite, who fought back against the assaults on the people and the environment of a Louisiana area filled with industrial toxins that became known as “Cancer Alley.” When Amos Favorite learned that his predominantly low-income parish had lost $94 million over the past 10 years because of tax breaks granted by the state to the chemical companies, he said, “We are subsidizing them for poisoning us.”

“We are subsidizing them for poisoning us.” — Amos Favorite

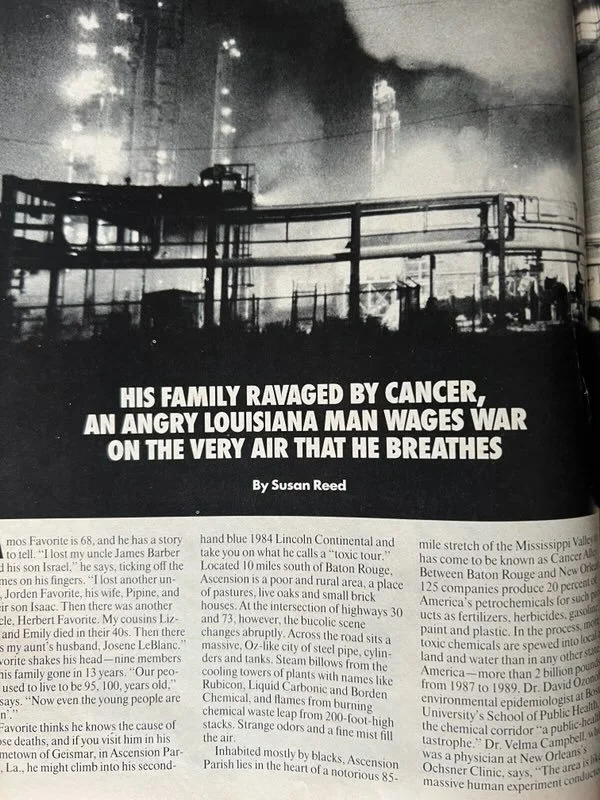

I’ll fight till I die to get zero discharges from these places,” says environmental activist Amos Favorite in the caption of this photograph in the March 25, 1991 People magazine article on him. He is standing near the Union Texas petroleum plant in Geismar.

Below: Front page of the article about Amos Favorite.

Mound of oil drums near the Baton Rouge Exxon Mobil Refinery along the Mississippi River. Geismar is about 25 miles away from Baton Rouge. Photo by John Messina - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Nature of being in a black, white & grey world

The visual artist is also a gifted writer whose After Color, published in May 2025, was winner of the Cosmographical prize for spiritual fiction. The novel is set in the early 2050s when humanity has lost the ability to see color.

The teenage protagonist Jade was born into the last generation of people who were able to see color. Some of the last gen, like her parents and grandmother, enliven their greyscale lives by remembering color. The adults discern fine gradations in the limited black-grey-white scale and have small parties where they try to imagine colors in their minds by, for example, imagining colors in art history books and exhibitions that they saw at Atlanta’s High Museum before coming colorblind. Her grandma hangs on through cloth swatches for quilts arranged in piles by color names assigned by her children before they lost color. The quilt motif, of course, has become saturated with meaning in other writings and other arts by African American women.

Growing up in the starkly black, white & grey scale world, Jade and her friends think the elders might be making too much of this non thing, “color.” These young people’s world could be like before color movies in the 20th century when people were mesmerized by “the silver screen” — luminosity made more brilliant by the absence of the color spectrum in the brick and mortar theatre. Jade’s philosophical classmate has another favorable interpretation of colorless being:

The ultimate goal of the universe is sameness, the ultimate unification…. Reduction as a form of optimization. Complexity wasn’t always an advantage, sometimes it was just unnecessary noise. This simplicity allows us to concentrate on the more important lessons and affairs of life. The deeper issues below the surface. Removing the stimulus of color forces us to focus on what is below color.

And the bi-racial Jade, when she finally does see the beginnings of color in a falling red leaf, and develops color sight, does have a moment when the racial implications of living in a color neutral world become apparent: “She understood why some people might prefer the simplicity of gray – why they might choose not to see the complicated truth of themselves.”

But mostly Jade is thrilled to gain the gift of color. The message unmistakably implied in this story is that humanity is living in a truly enchanting world through nature’s gifts of color. Gifts that even humanity has no full knowledge of; some animals see a far broader range of colors than we do.

The reader hopes that Jade will never become jaded like we are – we who are gifted with color sight and take this magnificent light spectra pretty much for granted.

As Jade explores her new world as a lone traveler, she marvels: the trees are at least a thousand shades of green.

Amos Favorite with fellow environmentalist activists.

Map by Alexrk2 - own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org

Malaika Favorite, MEDITATION II, mixed media, 40" x 30." Courtesy Baton Rouge Gallery

Malaika Favorite, Colored People Pool, mixed media on panel, 36 x 24”

Courtesy Baton Rouge Gallery

Malaika Favorite, Vanishing Habitat installation the Baton Rouge Gallery

The river flows through us making us one.

We are crabs skirting the borders of the river’s dress …

Lines from Malaika Favorite’s poem, “The River Flows Though Us”

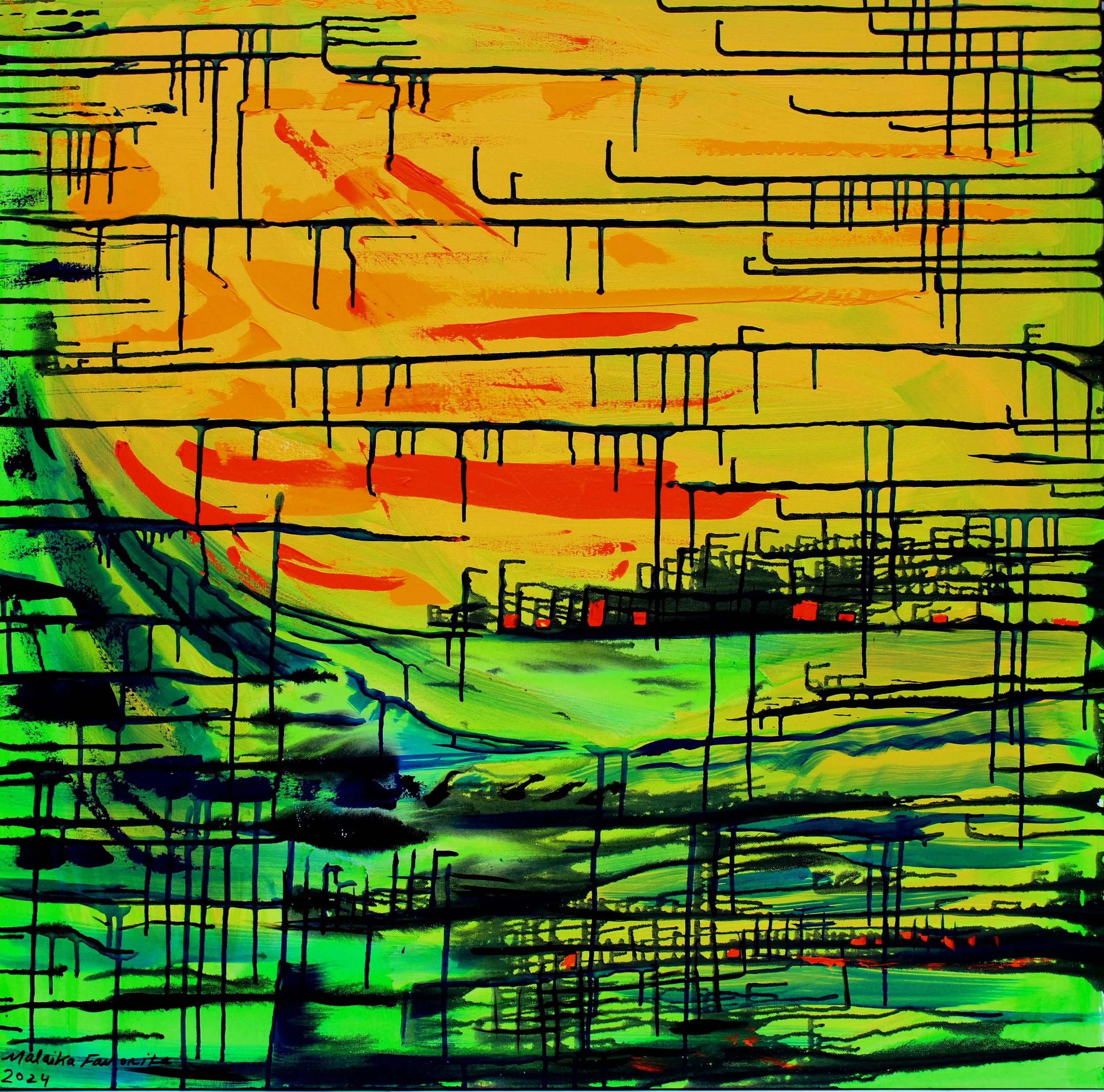

Malaika Favorite, RIVER ROAD, acrylic on canvas, 2024. Courtesy: Baton Rouge Gallery.

Malaika Favorite was born across the street from River Road in Geismar when the area was pristine.

She watched the encroachment of the industrial plants along the river and depicts then as fume-spewing silhouettes in the abstraction shown above.

Malaika Favorite, MEDITATION, mixed media, 40" x 30." Courtesy Baton Rouge Gallery

The past (Amos Favorite) and present (Trump regime) news about the simultaneous exploitations of lower income populations and natural environments to enrich the wealthy in the United States, felt like a cruel, hard punch to the gut as I contemplated it on the nation’s birthday.

The second gut punch followed a few days later when I learned about the Trump administration’s complete elimination of the agency that prevents as well as investigates industrial chemical contamination, allocating $0 (no funding) for its budget starting in 2026.

Barbara (Malaika) Favorite was born on River Road in Geismar, Louisiana, when that river ran completely unfouled. Now, through visual and literary arts, she continues the environmental activism that she learned from her father, Amos Favorite.

In 1958 Amos Favorite began working at Ormet Chemical, one of the first plants in Geismar, and among the numerous petrochemical plants and refineries cropping up along the banks of the lower Mississippi River.

Amos Favorite would go on to become a noted environmental, civil rights and labor rights activist. In 1986, He became president of Ascension Parish Residents Against Toxic Pollution and a founding member of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network. He worked to provide clean drinking water supplies to the Geismar and Dutchtown areas and also successfully fought to outlaw trucking of chemicals along portions of the state highway. His extraordinary level of determination was shown when he ran three times to represent his district in the state legislature, only to be defeated by more well-funded white candidates and his dogged but unsuccessful attempt to incorporate the community of Geismar.

Amos Favorite’s activism was nationally recognized when he was profiled in the March 25, 1991 People article. (Read the full text here.)

Barbara (later dubbed “Malaika” by a friend) spent her early childhood on the literal land without modern conveniences. Her mother, Rosemary Favorite, cooked on a black wood stove and scrubbed clothes by hand for Amos and their nine children on a washboard in the yard. No longer among the unsung heroines of the South, Rosemary Favorite is commemorated in Mailaika’s decorated washboards.

Amos Favorite raised hogs, and after completing trade school training in electronics on the GI Bill, moved his family into a home with the electrical wiring that he did himself.

Malaika recalls picking pecans with her siblings and friends, selling them to “Mr. Geismar” who owned the general store, and some of the kids using their pecan picking money to buy goods from Geismar. In the 1991 People magazine article, a woman who lived in the area said the pecan trees were no longer bearing fruit. The first degradation to the area during the anthropocene was the disruption and erosion of the Muskhogee people who lived in that particular part of the state.

Malaika’s grandmother had dark skin, long silver hair and said the indigenous people used to live in the Geismar area. The indigenous peoples of Lousiana “thought that the Europeans were gods … and they were willing and eager to please the great people who honored them with a visit…. It did not take long for them to find out that Europeans were not gods, but instead, were cruel and greedy men.” — Fred B. Kniffen, The Indians of Lousiana, Lousiana State University, 1945.

The history of appropriation and exploitation continued. The Geismar community is near the Ashland-Belle Helene Plantation which made a fortune off of sugar cultivation by enslaved people and had the "grandest and largest plantation house ever built in the state"). Other plantations in and around Geismar include the Waterloo sugar plantation where young Amos Favorite lived with his grandmother. The Waterloo plantation was separated from Mount Houmas Plantation by River Road.

In later life, Amos Favorite had multiple, serious health complications, not just the typical declines related to aging. Malaika can’t say for sure that his illnesses were directly attributable to working at the plant but she says that his contact with the chemicals was considerable. He climbed inside large tanks to clean out the sludge.

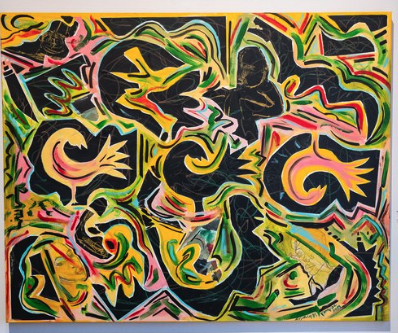

Malaika Favorite’s visual arts response to this history of degradations ranges from environmental justice activism to depictions of taking refuge and joy in the natural world — from Akoben: Call to Save the Earth, the large installation pieces shown in the River Flows Through Us poem by the artist below, and River Road which abstractly depicts the silhouettes of the industrial plants and their fumes, to the spiritual retreat in the bush of Meditation and Meditation 1, the delightful Colored People’s Swimming Pool (a bayou pond), and the ecstasy of Sitting Naked in the Rain.

Malaika Favorite’s environmental awareness is strongly tinged with lingering concerns. In October 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency found that black residents in southeastern Louisiana bear a disproportionate cancer risk from industrial air pollution. And the current Trump administration has significantly weakened the EPA through a combination of proposed budget cuts, regulatory rollbacks, and a shift in enforcement priorities.

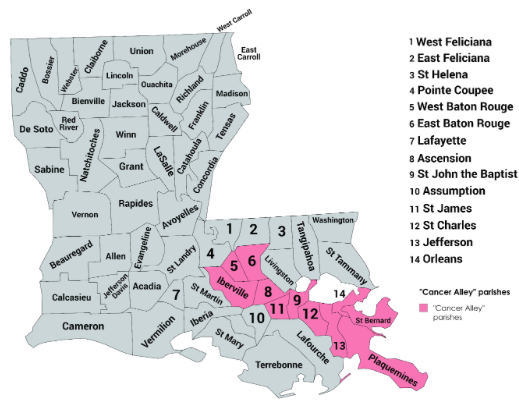

“Cancer Alley’ is the regional nickname given to an 85-mile stretch of land along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, in the River Parishes of Louisiana, which contains over 200 petrochemical plants and refineries. It doesn’t help the residents of that region to hear that dreadful name so let’s call it what it is: the Louisiana side of the lower Mississippi River delta.

As indicated by the broad range of her environmental expressions, Malaika Favorite does not let her environmental concerns diminish her exuberance and joy. She still loves to walk the river bank, fields and woods around Geismar.

“The environment is a gift,” Favorite says. “I need that connection. I don’t want to live in the city. In my walks I continue to be amazed. I find so much that could easily be overlooked – so many little things like small, red winged creatures. I pick up and see how complicated little things can be. And the wild grass – I wonder what properties it has that could be curative or be used in some other way. Every day is a different painting. Every sky, a different abstraction.”

Favorite returned home after living in Atlanta and Augusta GA for 27 years. She shoots lots of views of the area around Geismar as a wellspring of inspiration for her art and as replenishment for her energies to care for her mother, now 95, who has dementia.

While Favorite abhors the industrial transformation of the pristine River Road area across the street from where she was born, her art aims to highlight both the beauty of the river and its environs and the destruction humans have inflicted upon then. So a recurring motif in her colorful mixed-media works on canvas, wood and metal is the iconography of an intimate relationship with nature … and, very importantly, “nature” that encompasses people too.

“It is all art!,” Favorite exults, referring to people. “God, I appreciate your sculpture! We are living art even though we don’t realize it. We would appreciate each other more if we did. The intricate cell structures inside of us — there are paintings everywhere!”

She expressed her strongly conflated environmentalist-humanitarian views when referring to her 2022 exhibition at the Baton Rouge Gallery: “This series of works focus on our responsibility to each other and the environment we share…. It is a reminder to love and appreciate each other and use our natural resources with respect and appreciation by giving back to the earth and taking care of those who need our attention. I am everything and everything is me. You are everything and everything is you. ”

Malaika Favorite carries forth her father’s environmental awareness and activism in her visual arts work and creative writing.

Below: Her parents, Rosemary and Amos Favorite.

Amos Favorite in front of machinery used to lay pipe lines on his home property. Plumbing had finally become available in that part of the parish.

Map of Cancer Alley

by Patapsco913 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 (Wikimedia Commons)

Geismar is in parish 8 (Ascension parish)

Malaika Favorite, AKOBEN: CALL TO SAVE THE EARTH, mixed media, 30" x 40." Courtesy Baton Rouge Gallery

Malaika Favorite, SANKOFA, mixed media, 48 x 60." Courtesy Baton Rouge Gallery

Malaika Favorite, THE GOLDEN HOUR, 40" x 30"

Courtesy Baton Rouge Gallery

Malaika Favorite, SITTING NAKED IN THE RAIN, mixed media, 24" x 18.” Courtesy Baton Rouge Gallery

Malaika, what do the strips of “rain” say?